Ms.Sapna surin, Johnson Topno, MsSailabala and Mr.Manoj Kindo

Study conducted in FY 2020-21

Abstract

Structure of the Report : Section I highlights historical background, Provisions of FRA and National & State performance in its implementation . Identified bottleneck of c hallenges and gaps in the State.

Section II

discuss on Potential Areas of FRA beyond the statistical figures of recognition of the rights.

discuss the Charter of Demand & Recommendations on effective imp lementation of FRA 2006 in the State. Scope of convergence in coordination with multiple key stakeholders in the state . Key highlights of the pandemic crisis of COVID 19 and its implication on these tribal and forest dwellin g communities

Key Facts

- Jharkhand has extend of potential forest land under FRA (52,36,400 acre) among which only recognized 4.91% (2,57,154 acre)

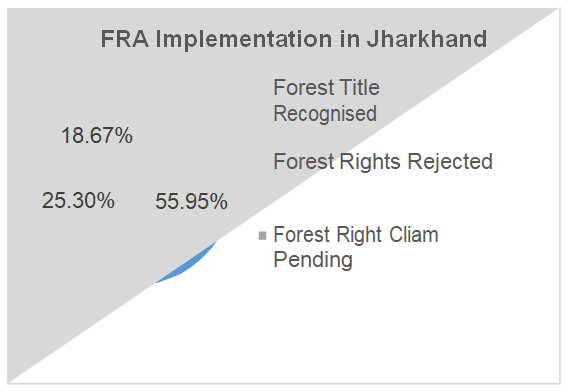

- In 2019, state performance in FRA states 55.95 % of IFR + CFR titles recognized, 25,30% rejected, 18.67% pending for review at multiple levels.

- last year (2019), it was only 1813 IFR and 14 CFR claims recognized across 24 districts in state

- Jharkhand’s average recognition (2.56 acre) is equal to the national average (2.19 acre) for IFR but far below than other states performance like Maharashtra (16.58 acre), Madhya Pradesh (6.47 acre) and Tripura (4.85 acre)

- For CFR average recognition ( 49.31 acre) is lower than the national average ( 115.62 acre) and far below than other states performance Maharashtra (386.32 acre) (Madhya Pradesh(52.39 acre) and Chhattisgarh (92.78 acre)

The Promise

- The bare minimum estimated potential forest area over which Community Forest Resource (CFR) rights can be recognized in India (excluding five north -eastern states and J&K) is approximately 85.6 million acres (34.6 million ha). And Jharkhand state s approximately 5.26 million acres (IFR & CFR).

- Rights of more than 200 million Scheduled Tribes (STs) and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (OTFDs) in over 170,000 villages are estimated to get recognized under FRA across India. Jharkhand only recognized 55. 95% (61,970 –IFR & CFR out of 1, 10, 756) of the total potential claimants in the State.

The Performance

In 10 years, only 3 per cent of the minimum potential of CFR rights could be achieved. In Jharkhand its only 4.91% of the minimum potential of IFR & CFR rights being recognized.aggard states: Assam, Bihar, Goa, Himachal Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand, Haryana, Punjab and Sikkim

Low performing states : Rajasthan, West Bengal, Karnataka and Jharkhand

IFR focused states: Tripura and Uttar Pradesh

CFR laggard states (those which have implemented Individual Forest Rights (IFRs) and Community Rights (CRs), but have ignored CFRs, the most important rights): Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Chhatti sgarh

Better performing states : Maharashtra, Odisha, Kerala and Gujarat (only in Scheduled V areas)

Reasons for Poor Implementation of FRA

• Absence of political will in State Government• Lack of effort to build capacity in the State nodal agency, the Ministry of Tribal Welfare Department

• Opposition by Department of Environment , Forest & Climate Change and forest bureaucracy, including by passing the CAFA, support to JFM and VFRs, constant opposition at the ground level

• Poor investment in implementation and its monitoring by State governments

Way Forward

• Marshal political support to Implement FRA in State• Establish Coordination and Clear Instructions to the forest bureaucracy and Department of EFCC to respect Parliament’s authority and stop obstructing FRA implementation;

• Undertake implementation in mission mode with clear Budgeting Support;

• Strengt hen State Nodal Agencies to implement FRA by supporting with FRA Cell

• Ensure effective monitoring systems at State levels

• Initiate awareness programmes on a large scale and build capacity of FRCs and the gram sabha;

• Develop an Inter -Departmental p rocess for Department of EFCC and other relevant Departments to resolve laws, policies and programmes conflicting with FRA and coordinate for integrated Model of Social Security and Empowerment of these forest dwelling communities in State.

• Strengthen Institute mechanisms to ensure unhindered exercise of CFR governance by the gram sabha after recognition and assertion of rights

SECTION I

Historical Background

The tribals who are commonly known as ‘Adivasi’ or ‘Indigenous’ people or ethnic minorities who constitutes a sizable 8.6% of India’s total population 1 had historically a symbiotic relationship between their tribal life and the forest resources . The tribals who reside on forest were totally dependent on forest produce such as food, fuel, fodder and even medicine for their day to day living . Their cultural life, religion of believes and festivals revolved around the forest as the ritual culture of worshiping natureIn the country, it was well known that the forest dwe lling scheduled tribes do reside on their ancestral lands and their habitat for generations and from times immemorial and there exists a spatial relationship betw een the forest dwelling scheduled tribes and the biological resources in India. They had been integral to the very survival and sustainability of the forest eco system of biodiversity, including wildlife. And cannot be ident ified as survival in isolation without the ecosystem and wildlife . Tribal economy is totally dependent on the agriculture but its dependency is on source of forest produce as their livelihood alternative. They have a symbiotic as well as naturally re inforcing relation with forest and historically associated with forest

In context to the country’s development, the states with rich resources has witnessed diverse forms of exploitations and displacement of people over decades because of developing projects and forcing injustice to the people residing on these lands. Jharkhand being one of these state do constitute 8.30% of total country’s

schedule tribe population residing and dependent on forest . The State counts 40% of country’s total minerals did faced 17,10,787 people displacement while acquiring 24,15,698 acres of people’s lands for setting up the Power Plants, Irrigation Projects, Mining Companies, Steel Industries’ and other development projects in State 2. The figure of displacement varies from 1.5 million to 3 million people 3. The state also witnessed high number of migrants especially with close to 5 million of its work ing age population between 2001 and 2011 who migrated to other states for better opportunities. In absence of agrarian crisis in the state and lack of rural employment opportunities about more than 1 lakh of working stranded migrants every year migrate to other states for better employment alternatives. Thus, leaving less hold of their families over existing resources and absences of power on forest resource rights being gradually encroached, alienated and diverted for other economic state development priorities’ without settlement of these dependent forest dwelling communities’ rights on forest land in the states .

Introduction to Forest Rights Act:

Acknowledging the historical injustice on these tribal forest dwelling communities’ rights ov er the forest resources’ in the country. In December 2006, both the houses of the Indian Parliament unanimously passed the historic Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 (referred as the Forest Righ ts Act (FRA)), a unique emancipatory law with the potential to transform the lives and livelihoods of more than 150 million Forest -dependent people. Rules under the Act were notified in December 2007, and from 1st January 2008, the Act became effective for implementation in all the states of India excepting Jammu and Kashmir. The Act states in its Preamble that rights of the Scheduled Tribes (STs) and the Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (OTFDs) on their ancestral lands and habitats were not recogni zed in the consolidation of state forests during colonial rule as well as in Independent India . This resulted in historical injustice to these communities who are integral to the survival and sustainability of the forest ecosystem. Recognizing and vesting of thes e rights is, thus, the primary objective of this Act.The law vests a number of rights over forest lands with forest dependent Scheduled Tribes (STs) and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (OTFDs), including individual rights over forest lands, community rights and the rights to protect and manage Community Forest Resources within traditional or customary boundaries o f the village. The most critical right, which has a bearing on forest governance and the welfare of tribal s and forest dwellers, is that of C ommunity Forest Resource Rights (CFRR).

These rights provide hold of individuals rights over forest lands under o ccupation for habitation / self - cultivation, community rights over forest resources, the right to own, access, use and dispose of al l minor forest produce (including bamboo), and the right to protect, regenerate, or conserve or manage forest resou rces as community forest resources for sustainable use. This is to facilitate the protection of forests and biodiversity, while ensuring livelihood and food security of the forest dwellers, thus seeking to secure traditional rights over forest land and community forest resources, and establish democratic community -based forest governance. The Act also establishes a three -tier, quasi -judicial system of au thorities and framework of procedures, for

determining the nature and extent of the rights. It recognizes Gram Sabha as the authority to initiate this process by receiving claims, verifying the same, passing appropriate resolutions and then forwarding them to the Sub-Divisional Level Committee (SDLC) for further action. The SDLC is mandated to examine these resolutions, prepare a record of forest rights, and forward the same to the District Level Committee (DLC) for the final decision.

Aspirations of the Law

FRA emerged as a legislative response to a national grassroots movement to record the rights of forest dwelling communities whose rights were not recorded during the consolidation of state forests in the colonial regime and in the post -Independence period, many of whom have been displaced for industrial and conservation projects without rehabilitation due to being labeled ‘encroachers’ on forest land.Section 4(5) of the Act requires that no member of the forest dwelling Scheduled Tribes (ST) or Other Traditional Forest Dwell ers (OTFD) shall be evicted or removed from forest land under his occupation till the recognition and verification process is complete.

The process of recognition and verification laid out in FRA is currently the only legal process for determining the genuine right holders and their rights on forest land. FRA recognizes 14 pre-existing rights of forest dwellers on all categories of forestland, including Protected Areas. The major rights are:

Individual Forest Rights (IFRs) and Community Rights (CRs) o f use and access to forest land and resources

Community Forest Resource (CFR) Rights to use, manage and govern forests within the traditional boundaries of villages

Empowerment of right -holders, and the gram sabha, for the conservation and protection of forests, wildlife and biodiversity, and their natural and cultural heritage (Section 5, FRA)

The law is significant seeks to democratize the process of rights recognition by making Gram Sabha the key authority in the rights recognition process. FRA has a lso created space for Informed Consent 1 of the Gram Sabha for diversion of forest land. Thus, providing these rights and the Gram Sabha’s empowerment, taken together, can transform and radically democratize forest governance and conservation regimes in In dia. For the millions treated as ‘encroachers’ on their forested habitats and others who were deprived of any sa y in the matters related to the fate of forests on which their cultures and livelihood depend, FRA implies re stitution of their citizenship rig hts and a right to live with dignity

The CFR provision, taken together with Section 5, is the most significant and powerful right in FRA, as it recognizes the Gram Sabha’s authority and responsibility to protect, manage and conserve its customa ry forests for sustainable use and against external threats

Overview of State Performance :

The State of Jharkhand came into existence on 15th November 2000 after the reorganization of the ers twhile unified Bihar. Situated in the eastern part of the country, Jharkhand covers an area of 79,716 sq . km, which is 2.42% of total geographical area of the country. Covering 22,945 sq. km as forest land close to 30% of the state’s geographical area. Its total population is 32.9 6 million, approximately 26% as scheduled tribes (Census 2011). The state is immensely rich in its mineral resources; 40% of the total minerals of the country are available in Jharkhand4.As per the Champion & Seth classification of the Forest Types (1968), the forests in Jharkhand belon g to two Forest Type Groups which are further d ivided into eight forest types. Various ethnic groups such as Munda, Oraon, Ho, Santhal, Paharia, Chero, Birjea, Asura and others live in the State and follow varying pr actices of agro- pastoralism. Traditionally, these indigenous people have symbiotic relationship with forests. Loca l festivals like Sarhul and Karma are customarily related with worshipping of trees. Jharkhand has a r ich variety of flora and fauna which has its present across 23,605 sq km of Recorded Forest Area (RFA) in the State among which 4,743 sq km area counts as Reserved Forests, 17,738 sq km as Protected Forest area and 320 sq km as Unclassed Forests land. Total carbon stock in the state estimates to be 178.01 million tonnes, which contributes 2.50% of the total forest carbon of the country . The 19th Livestock census 2012 has reported a total livestock population of 18.05 million in the State. (ISFR, India State of Forest Report. Vol2 (Jharkhand 2019)

In Jharkhand, during the period 1st January 2015 to 5th Feb 2019, a total of 690.87 hectares of fore st land was diverted for various non -forestry purposes under the Forest Conservation Act, 1980 (MoEF & CC, 2019). One National Park and 11 Wildlife Sanctuar ies were established in the Protected Area network of the State covering 2.74% of its geographical area which currently needs to be review ed as priority of FRA rights recognition, settlement & rehabilitation of the people being displaced in the se forest ar eas. Recognizing of individual & community forest rights , it is estimated that rights of over 200 million STs and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (OTFDs) in over 170,000 villages across the country should be recognized under the FRA, 2006, mostly through the Community Forest Resource Rights (CFR). The minimum area that can potentially be claimed under t he CFR in Jharkhand is estimated to be 5.26 million acres (CFR-LA, 2016).

The FRA implementation was deliberately brought under the jurisdiction of M inistry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA) to ensure that recognition of rights has speedy trial in convergence with forest and revenue department , whose powers have been curtailed by democratic provisions in the FRA. In almost all states, the nodal depa rtment for FRA is the Tr ibal/ Social Welfare department in coordination with the forest department for effective mechanism of implementing t he FRA’s rights recognition process , but the forest department has either appropriated or been given effective control over the FRA’s rights recognition process5

Figures of FRA performance in the country from different states and in reference to the recent Supreme Court order of 13th Feb, 2020, MoTA instructed respective states for review recognition of IFR & CFR claims in state and promote speedy trial of its settlement of the rights. Thus, it essential to understand the true spirit of FRA 2006 provisions and intervene for a n integrated model of coordination and convergence between Tribal/ Welfare, Forest , Revenue & Rural Department in light to the best practices available of other states such

as Gadchiroli & Nandurbar district s in Maharashtra, Kandhmal and Mayurbhanj districts in Odisha, Narmada and Dangs districts in Gujarat, and Thrissur in Kerala and Gariaband district in Chhattisgarh, where administration has successfully acknowledged the recognition of Community Forest Rights (CFR) & Community Forest Resource Rights (CFR) under the governing authority of respective gram sabha as per the provision of the Act . Where gram sabha is successfully ensuring its management and convergence plan ning in coordination with the state development entitlements rights on the recognized forest land with sustainable livelihood model of value chain and aggregation business on NTFPs/ MFPs which resulted into potential and the resultant improvement in communities food security and economic conditions of living and can be seen in success stories across the country as following

• Soliga tribes in Biligiri Rangasw amy Temple Wildlife Sanctuary in Karnataka reclaimed their traditional and sacred areas under FRA. In 2004, the Supreme Court had banned sale of forest produce, and in 201 1 their habitat was converted into a tiger reserve.

• Many villages in Gadchiroli di strict of Maharashtra used their rights under CFR to collect and sell bamboo and tendu leaves directly. In 20 16, as many as 20 village soled tendu leaves for Rs.1.54 crore.

• More than 10,000 villages in Odisha are part of a self -initiated network which wor ks along with the government to implement FRA, and regenerate and conserve their forests.

However, despite its intention and potential, the implementation of FRA has failed to achieve the ta sks and objectives it set out to do. In many cases, CFR titles w ere given to facilitate developmental processes instead of recognizing rights, as vested under CFR. In such a scenario, the rights of Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTG), Nomadic Tribes, Pastoralists, Fisher Folk, and Women have remained absolutely neglected, even excluded6.

The situation becomes more serious due to the economic and developmental policies of subsequent governments which have been pushing for diversion of forest land for mining, industrial corridors, and other mega projects. Since the enactment of FRA, 204,000 hectares of forest land have been diverted for development projects across country. Most of the diversions have taken place without the compliance of the Act or the consent of Gram Sabha. A joint committee report by MoEFCC and MoTA in 2010 acknowledges this. The diversions have often led to violent conflicts with the state administration, further aggravating human rights violations of these communities.

However, unlike the tribals, the OTFDs have not only to prove that they were living or dependent on forest land prior to 13 th December, 2015 but also have to provide 75 years of evidence to claim their tenure rights under FRA. Such stringent provision for the OTFDs has led to huge discrimination against the OT FDs in the recognition process. There is no database at the national l evel on the social category of beneficiaries under FRA but information obtained from FRA cell of various states, it is found that the recognition of individual forest rights for OTFDs is between 5 to 10% across the country 7

Potential of Forest Rights Ac t and Its Performance in Nation & State of Jharkhand:

> The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 or FRA was a landmark legislation that sought to restore the rights of forest dw ellers over land, community forest resources and habitats, and the governance and management of forests. A close look at the pot ential of FRA and its performance over the last one decade in the country and Jharkhand which reveals that millions of forest dwellers have been deprived to get the benefits of this act, especially tribals. The effective implementation of FRA would result in recognizing more than 5 million acre of forest area for the forest dwellers across Jharkhand.The FRA has been in force for the last twelve years. However, the implementation of the Act has not been effective and only 17 % of the total potential forest are a across the country has been recognized under forest rights (Sahoo & Sahu, 2018). The Monthly Progress Report to FRA complied by the Ministry of Tribal Affair till 31 st Oct, 2018 shows that a total number of 18,93,477 claims (18,21,413 IFR and 72,064 comm unity claims) have been recognized over 17,857,026.94 acres of forest land (46,73,117.58 acres for IFR and 13,183,909.36 acr es for CFR claims) by the authorities across India. It is also important to note there that the scale of FRA im plementation is neither uniform nor at the same pace across India.

The top five States, namely Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Tripura and Maharashtra constitute 71% of total recognized forest rights claims and also 76 % of total forest lands recognized across India til l 31st October, 2018. Till 31st March, 2019, out of total 1, 07,032 IFR and 3724 CFR claims, total 59,866 and 2,104 titles under IFR and CFR respectively have been approved in the State of Jharkhand under FRA as per records of MoTA Report8. In comparison to 31st March, 2018 these figures was 1,05,363 and 3,667 titles approved under IFR and CFR respectively 9. Although, the number of claims approved showing a progress and have increased but still it is only the half of the total submitted claim s and yet 1, 05,363 IFR and 3,667 CFR claims are pending as on 31 st October, 2018 as shared data by Tribal Welfare Department, Government of Jharkhand. Thus, last year 2019, it was only 1813 IFR and 14 CFR claims being recognized cross 24 districts in Jharkhand as per Govt. record in comparison to 2018 ( 1669 IFR & 57 CFR claims recognized)

The estimated potential target across 24 districts in the state is 86,45,042 of total tribal population resigning in 58,20,065 acres of total forest land having total potential of 46,51,482 acres of forest rights recognition under FRA in Jharkhand 10.

The following tables and figure highlights overall district -wise status of FRA implementation in Jharkhand 11.

| Name of State | Extent of Potential Forest Land under FRA (IFR+CFR) ( in Acre) | Extent of Recognized Forest Land under FRA (IFR+CFR) ( in Acre) | Percentage (%) of Recognized Forest Land against Potential Forest Land under FRA on 31 st March 2019 |

| Row 2, Jharkhand | Row 2, 5236400 | Row 2,2,57,154 | Row 2,4.91 |

Table 2: Performance

| No. of Claims Received | No of Titles Recognized | No of Claims Rejected | Forest Land Recognized (in Acre) | |||||

| IFR | CFR | IFR | CFR | IFR & CFR | IFR | CFR | ||

| 1,07,032 | 3,724 | 59,866 | 2,104 | 28,017 | 1,53,395 | 1,03,758 | ||

| Total | 1,10,756 | 61,970 | 28,107 | 2,57,154 | ||||

Average recognized CFR land in Jharkhand is 49.31 acre

Percentage of potential forest area recognized – 4.91 %

- Forest right titles recognized – 55.95 %

- Forest right claims rejected – 25.30 %

- Forest right claims pending – 18.67 %

Which seems to be to be found increase in recognition of IFR as per 2018 performance and decrease in CFR recognition. Even pending claims of IFR & CFR figures of 2019 also increase in compare to 2018 in the State.

The above analysis and empirical evidence 12 from field reveals that the nature and extent of forest rights act implementation in Jharkhand is very low and abysmal. The provision under the Act states that Section 4 (6) of FRA enables forest dwellers to claim up to 4 hectares (10 ac res) of land under individual or common

occupation for habitation or for self -cultivation. At the same time it is clarified by the MoTA that the four hectare limit specified in Section 4 (6) applies to rights under 3 (1) (a) of the Act only and not to any other rights under Section 3 (1) such as conversion of pattas or leases, conversion of forest villages into revenue vil lages etc. In this context, it is important to mention that the traditional and customary laws in Jharkhand recogn ize the rights of forest dwellers over land not limited to ten acres and forest resources in different forms under diverse laws, such as Chotanagpur Tenancy Act 1908, Santhal Pargana Act 1049 and Wilkinson Rule 1837 13.

But keeping aside the recognition and implementation of th ese laws, the state administration has failed to recognize the submitted claims under both IFR and CFR claims and in comparison to other states never have prioritized the CFR and CFRR rights as recognition provision to be ensured under the Act implementati on in State as mentioned earlier, in information being obtained from FRA cell of Maharashtra, Odisha and Chhattisgarh. If we see the average IFR recognition performance, Jharkhand is 2.56 acre of IFR recognized which is equal to the national average of 2.1 9 acre but far below than that of other states like Maharashtra (16.58 acre), Madhya Pradesh (6.47 acre) and Tripura ( 4.85 acre) as average IFR recognitio n respectively. In the average recognized of CFR area in Jharkhand its 49.31 acre which is lower than that of national average with 115.62 acre and in comparison far below than the other states like Maharashtra (386.32 acre), Madhya Pradesh (52.39 acre) and Chhattisgarh (92.78 acre) 14

There are multiple reasons in the state for such dismal performance in the implementation of FRA. Among which some that includes are:

- Lack of political will and coordination among the nodal agency i.e Social Welfare Dep artment and other key departments i.e Forest, Revenue & Rural of Jharkhand

- Introduction of conflicting laws at the state level to subvert the rights of forest dwellers

- Opposition by Department of Environment Forest & Climate Change and forest bureaucracy, including by passing the CAFA, support to JFM and VF Rs, constant opposition at the ground level

- Poor investment in implementation and its monitoring by State governments and effort to build capacity in the State nodal agency, the Ministry of Tribal Welfare Department

- Capacitate the knowledge of authorized officials, provide the supportive records under the provision of the Act (maps, Govt. Amin etc.) and documents etc.

- District level to strengthen the functional mechanism of the SDLC & DLC for reviewing the processes of recognizing the submitted claims

SECTION II

Forest Right Act, 2006 needs to be looked beyond its priority of recognition of tenurial security rights as a possible model of empowerment of these forest dwelling communities with resource rights which develops for them a multiple potential areas of sustainable, integrated approach of adaptive climate resilience response and ensure them with justice and authori ty of ownership. Also strengthening their community based forest governance for promotion of their livelihood opportunities with value add for minor/ non-timber forest produces. Following are some of the se potential areas under provision of FRA with examples of best practices across different states :

- Democratized Model of Forest Governance CFR Rights Recognized 1800 hectares of Forest land by MendhaLekha village in Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra. Gram Sabha initiated forest governance and management processes with financially viable, socially equitable and ecologically sustainable Model. In Payvihir village of Amravati district of Maharashtra received CFR title in 2012 and devised forest use and protection rules leading to forest conservation and increased production of grass, custard apple and tendu leaves.

- Wildlife Conservation Plan 33 CFR title settlemen ts in BRT Tiger Reserve of Karnataka came together to formulate a tiger conservation plan with Forest Department. In Gujarat’s Narmada distric t, more than 60 villages initiated simple governance systems to protect, conserve and manage forests. In Simlipal Tiger Reserve of Odisha, villages with CFR titles have devised simple, rule -based adaptive governance systems for their CFRs, and are now protecting their forests.

- Protection of Forest Biodiversity: Many communities across the country have successfully stopped commercial forestry operations in their CFRs. This has increased biodiversity leading to greater foo d security. These communities include the dense forests of Chilapatain the northern Bengal Do oars— the foothills of eastern Himalayas. Baiga community of Dindori district in Madhya Pradesh has similarly banned coupe cutting by the Forest Department. This has increased the availability of dive rse forest foods.

- Convergence of Development Programmes :200,000 individual households holding forest land titles in Odisha was supported through convergence programmes related to housing (IAY), land development (MGNREGA), irrigation and horticulture. In over 200 villages in Gadchiroli, Amravati, Gondia, Yavatmal, Nandurbar and Jalgaon districts of Maharashtra, convergence programmes for individual title holders, as well as for forest conservation and management plans for CFRs, have led to remarkable change in livelihood and employment security.

- Transforming Forest Governance: The recognition of forest resource rights will ensure in protecting socio -cultural relation of forest dwelling communities with forest. Access to forest resources providing their cultural identity and build connection of effective conser vation and management of these natural resources with traditional ecological knowledge.

- Creating Community-Based Forest Governance:The space creates democratic local adaptive forest governance and empowers the gram sabha to prepare conservation and man agement plans. Transfer of jurisdiction of CFRs to the gram sabha will boost creativity and leverage disperse local knowledg e of forest dwellers to effectively manage, govern and restore forests at a low cost with effective fo rest governance and restoratio n by the gram sabha which is already being practiced in shared example of villages of other states.

- Potential for Livelihood Security, pove rty alleviation and development: FRA has extraordinary potential for ensuring livelihood security and poverty allev iation through sustainable and community - based management of forests for these people. The Act offers opportunities for poverty alleviation through forest product harvesting, processing and forest enterprises, and transfer payments to the gram sabha for reforestation, carbon sequestration and provision of ecological services. A significant opportunity lies in the convergence of FRA with development programmes such as MGNREGA , Cash trafer, Jan Dhan Yojana, IAY etc. Till now, FRA’s implementation has been li mited. But even that much has made startling and powerful changes which can be seen with field report ed cases of Maharashtra, Gujarat & Odisha where tribal and OTFD gram sabhas have earned tens of lakhs of rupees each from the sale of bamboo and tendu leaves (Narmada district in Gujarat, Gadchiroli and Chandrapur in Maharashtra 15), and through largescale convergence of FRA with programmes such as IAY and MGNREGA (Kandhamal and Mayurbhanj districts in Odisha).

- FRA and Food Security: The role of forests in food security and nutrition is being recognized globally. Food from forests and tree -based systems is likely to continue to form an essential part of household strategies to eliminate hunger and achie ve nutritionally balanced diets 19 . Food from forests provides micronutrients and co ntributes to dietary diversity 20 . It also provides nutritional sufficiency and a “safety net” during periods of other food shortages caused by crop failure and durin g seasonal crop production gaps. FRA has the potential to improve the status of food security of millions of forest - dwelling poor and tribal communities by recognizing their age -old tenure and occupational rights of land and forest products. IFRs, through recognizing occupancy rights and allowing investments on the recognized land, can contribute to the food security of margin alized forest dwellers (ibid). Similarly, recognition of traditional and sustainable shifting cultivation practices support food security. The transfer of forest governance responsibility from forest department to the communities also creates potential for sustainably managing forest landscapes for food, nutritio nal production and livelihoods 21.

- Gender Justice: FRA gives significant emphasis to gender equity. It requires that land titles for individual forest rights be issued in the joint names of both spo uses, or in the name of a single household head, irrespective of gender. The Act, thereby, equally entitles women -headed households. In case of community rights, including the critical CFR right, all adult women implicitly gain equal right to access and participate in gram sabha decisions related to CFR management. FRA also mandates the representation of women in the Act’s implementation in institutional structures of the gram sabha, FRC, SDLC, DLC and SLMC. At least one-third of the minimum quorum for gram sabha meetings must consist of women and at least one -third of FRC members must be women. In SDLCs, DLCs and SLMCs, at least one of the elected members must be a woman. Thus, FRA creates space for inclusion of women in forest governance and decision makin g through secure forest rights and representation in the institutional structure. However, there is a need for more work to challenge deeply entrenched processes of patriarchal dominance including state institutional structures, and socio -cultural practices and taboos22.

- Democratization of forest diversion : Earlier, decisions on forest diversions were taken without the involvement of the affected local communities. FRA adds a new dimension to this decision -making process. The Act empowers STs and OTFDs to refuse consent for any project or process that threatens the forest, wildlife or biodiversity, and adversely affects their cultural and natural heritage. Sec tion 4(5) of FRA provides that no ST or OTFD can be evicted from forest land unless the process of recognition and vesting of rights is complete. A circular by MoEFCC dated August 3, 2009 insists on “informed consent of the gram sabha affected by diversion of forest land”. This is a dramatic gain f or a country where over 55 million people are estimated to have been displaced by development projects since Independence, often forcibly 23. And also in Jharkhand where in inviting of multiple development projects have also unable to ensure the justice to the people’s settlement and rehabilitation rights in affected land diversion and mining areas across the districts with effective utilization of District Mineral Fund.

- Protection of Cultural and Natural Heritage: By democratizing forestland diversion, and by giving gram sabha the decision -making authority, FRA has provided legal space to local communities for the conservation and protection of areas important for their livelihood and sustenance of their socio - cultures practices and biodiversity. Communities in different parts of the country have successfully used FRA provisions to protect forests and their bio -cultural habitats.

- Dongria Kondhs, a PVTG of Odisha, in a case against bauxite -mining proposal in the forests of its sacred Niyamgiri Hills 24

- Communities of the Kashang valley in Himachal Pradesh 25

- Mahan forests of Madhya Pradesh 26

- Communities in Murbad taluka of Maharashtra protesting against Kalu Dam

- Gram sabhas in Hasdeo Arand forests of Chhattisgarh against coal mining 27

- Forest Rights: Charter of Demand & Recommendations

In context to the historical injustice under the government policies in both colonial and independent India toward tribal forest-dwelling communities, whose claims over their resources were taken away during 1850s. And with the effort of FRA 2006, the administration has recognized their rights in spirit of sustainably protect ing the forest through traditional ways along with providing these tribes a means of livelihood. It expands the mandate of the Fifth and the Sixth Schedules of the Constitution that protect the claims of indigenous communities over tracts of land or forests they inhabit through identifying IFR and CFR tries to provide inclusion to tribes. And ensure their democratic forest governance by recognizing Community Forest Resource Rights (CFRR) and ensure the rights t o manage their forest on their own. Thus, it’s important to work for effective implementation of the FRA, 2006 in State in continuation to its potential status till date and build the possible road map as guideline for way forward strategy in coordination & convergence with inter -departmental dialogue, consultation with non-profit organization closely working on FRA recognition and academic institutes .

In 2013, with support from CSOs, 18 gram sabhas in Gadchiroli, Gondia and Amravati districts collected and sold tendu leaves worth crores of rupees from their CFR 16 areas. In BiligiriRangasw amy Temple (BRT) Tiger Reserve in Karnataka, five gram sabhas, which have received CFR titles, have established a honey value-addition center 17 . In Shoolpaneshwar wildlife sanctuary in Gujarat, sustainable bamboo harvest by communities from their CFR areas have yielded large incomes and wage employment. Rights recognition could potentially wipe out persistent poverty from forested heartlands of India 18.

Thus, addressing the priorities of the FRA provisions and its best sprit and how other states administration has built the possible potential areas for empowering the scheduled tribes and other traditional for est dwellers’ rights over forest land and resources. The state of Jharkhand too can overlook the integrated approach model of empowering these communities’ right s and develop a convergence model for recognition of individual and community forest rights especially emphasizing the recognition of community forest resource rights (CFRR).

SECTION III

Following are some of the areas of recommendations and charter of demand being proposed for effective implementation of FRA in State :

1. There should be a dedicated one Nodal Department ( Tribal Welfare) to develop program , policies and review the implementation of legislations pertaining to T ribal Rights and Welfare in the state. And establish effective inter -departmental coordination in state to review the status of pending claims to be recognized, issue circular/ orders/ guidelines on regular bases for smooth functioning and strengtheni ng of the mechanism of coordination with District & Sub Divisional Level Committees.

2. State Forest Rights Act (FRA) Cell would be established as Secretariat under Nodal Department (Tribal Welfare) to support the handhold ing day to day functioning & coordination of FRA implementation as resource centre. As support institute reinforce regular ity in review meetings at State Level Monitoring Committee, District Level Committee & Sub Divis ional Level Committee . FRA Cell with pool of resource budget allocation act as resource centre for developing capacity building & training programs, tools for mass awareness generation on FRA in state, avail the resource document s (forms, revenue, cadastral maps etc.) at district in coordination with Revenue & F orest department, promote fund raising, ensure proper documentation of record keeping for regular review & reporting needs in State and ensure other follow up coordination and handholding support to Nodal Department to Central Ministry (MOTA) . And closely coordinate with other institutes in states as notified.

3. Adaptation of draft State SOP being developed in consultation with CSO as guideline for ensuring the facilitation of provision under the FRA. Create platforms for CSO collaboration to have consultation with State Administration to discuss way forward road map for effective implementation of FRA in State.

4. Implementation of the Forest Rights Act, 2006 should priorit ize the rights recognition of Community Forest Resource Rights in the State for empowerment of tribal sustainable growth in an integrated approach with inter –departmental coordination and convergence for channelizing provisions of social security & protection entitlements rights

5. Ensure provision of notification of other non -government organizations’ & academic institutions in state for ensuring collaborative state level research studies to analysis the current facts on state context of FRA potential in 24 districts, i dentified areas of handholding support that can bridged in its review process (DLC & SDLC) along with respective CSOs district wise , support in empowering the grams sabha and other community based institutions for forest governance for sustainable livelihood opportunities etc.

6. State Administration in Jharkhand should immediately notify the rules to PESA in 5 th Scheduled Area to keep the spirit of the Central law and ensure FRA implementation in these areas without any conflict o f laws. No displacement should take placed in the PESA area without settlement of the rights and all Government services should converge to improve the hum an development indicators in these region. Conversion of PESA area into urban authorities activities need to be stopped immediately for review in coordination with Department of Rural Development & Urban Development & Housing.

7. All Policies and programs t hat violate the letter and spirit of Forest Rights Act, PESA, SPTA and CNTA should be reviewed. And decentralized forest governance system with Gram Sabha should be encouraged by establishing the Gram Sabha as authorized operational body playing the centra l role in recognition of FRA rights. Without free and prior informed consent of Gram Sahba’s no diversion of forest land for non- forest purpose and displacement of forest dwelling communities should be permitted.

8. Ensure restoration of Community land/ Fo rest land that has been placed under land -banks without due procedure including land banks for C ompensatory Afforestation Fund (CAF), 2016 or for any purpose of industrial development and were diverted appropriately without forest dwellers’ consent.

9. Different welfare schemes and social protection entitlements rights of the line departments should be integrated for forest dwellers as well as for the land recognized under F orest rights Act through Gram Sabha and further engaged into post CFR management and convergence planning in coordination with Department of Forest, Environment & Climate Change .

10. Gram Sabha should be authorized to permit access rights to forest dweller to dispose NFTPs through gram sabha. Review orders under minimum support price and deregulat ion of existing Non Timber Forest Produce in coordination with Department of Rural Development and Forest, Environ ment & Climate Change.

11. Women’s role in agriculture and forest governance to be re cognized and given priority under Forest rights Act. Ensure recognition of joint entitlements’ under FRA. Policy spaces should be created to ensure women’s participation in Gram Sabha such as Women special G ram Sabha meeting before general meeting of the Gram Sabha to incorporate the resolution of the women’s meeting . Protection aspects of women rights should be promoted in state in coordination with Department of Women, Child Development and Social Security on Forest Areas.

12. Special priority to most vulne rable groups such as PVTG communities in state should be given with provision of habitat rights of them under FRA , special schemes and social protection entitlements’ provision should be promoted in convergence with inter -departmental coordination in State

13. The Aspirational districts should strengthen utilization of District Mineral Fund (DMF) in organized & planned process for the settlement & rehabilitation provisions’ in mining affected districts. The Rules need to ensure the communities have the data and knowledge to develop technical plans for improving livelihoods and environment of the mining affected communities.

Pandemic Crisis of COVID -19 on Tribal & Forest Dwelling Communities’ in State: Issues, Challenges & Recommendations

While COVID-19 impacts everybody cross the country , the implications on the poor and marginalized sections such as the daily wage labourers, forest dwellers and informal sector workers with inadequate economic and social safety nets is severe affected and will have long term consequences on their lives and livelihoods. This has turned this health emergency into a humanitarian crisis. The forest dwellers with s mall agricultural land holdings who often inhabit very remote and difficult terrains have been missing from the discourse. The lockdown is beginning to have serious implications on the Tribal and forest dwelling communities in India with contribution of th eir deprivation of food security concerns especially among tribals & PVTGs in remote forest areas are massive in the state.

Jharkhand with its remote forest -fringe villages, and about 300 million Tribals and other local population who depend on forest as their main source of livelihood and cash income f rom fuelwood and forest produce 28 including the particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs) , among which 73 percent of them wer e deprived as per the report of Socio Economic Caste Census 2011 . Agricultur e and Minor Forest Produces (MFPs) as their major sources of livelihoods has unfortunately suffered in this pandemic period of COVID 19 lockdown, which began in March, 2020 and coincided the peak hour of MFP harvesting season where people were prohibit ed to collect ion and selling of their produce s in local markets. Leaving the vulnerable need of cash support among these dependent tribal households especially the single women (widow & old age group). In additional to these, community members seek tempora ry employment under Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGA), as construction labourers in urban centers or as agriculture labour in adjoining villages . The reverse migration of these labourers from cities, with no job s and no source of incomes add to the tribal distress. Lack of wage labour opportunities, pending MNREGA payments from last year, no cash in hand or inflow of remittances for agriculture has created a situation of uncertaint y. So it’s essential to meet the immediate relief package and food supply through PDS in continuation in these remote areas inhabited by forest dependent communities even after the lockdown as urgent priority .

In light of the given situation, following are some of recommends that the state government can take into consideration to ensure that Tribals and Other Forest -Dependent Communities aren’t left behind with priority to the social security and protection entitlement rights in this pandemic situation:

Proper implementation of minimum support price (MSP) and procurement of MFPs:Minister for Tribal Affairs has already written to the Chief Ministers of 15 States and to the State Nodal Agenci es suggesting to procure MFPs at Minimum Support Price (MSP) and to coordinate with Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development Federation of India (TRIFED) for any support. TRIFED too has written to find ways to red uce the impact of COVID-19 on MFP based trade. Under the Pradhan Mantri Van Dhan Vikas Yojana, 15,000 29 VanDhan centres are to be converted into s ocial distancing cum livelihood centres to provide relief, ration and awareness to forest communities. However, these facilities are primarily to provide infrastructural support for procurement cum value addition to locally available MFPs. Till Dec 2019, 6 74 Van Dhan Kendras have been sanctioned and there is low utilization of the funds sanctioned and the reporting mechanisms on progress from the States are poor. On the positive side, the Chhattisgarh government has increased the MSP fo r mahua flowers from Rs. 17 to Rs. 30 per kg. This is much needed and a welcome step one which other states need to follow.

Clear guidelines need to be given regarding MFP procurement to the state nodal agencies such as the Tribal Development Co-operative Corporations (TDCC)/ state forest development corporation’s/ MFP f ederations, engaging local self -help groups (SHGs) to collect from individual collectors is also an option that can be explored, as also specifying regulations for private traders to protect the collectors from being exploited. The Van Dhan Centres or panchayat bhawans can be used for storage during this time till the produce is transported.

Effective measures should be taken to strengthen the health infrastructure, testing kits, labs and h ealth care professionals like pathologists, trained doctors and nurses must be hired in these regions. In the m ining affected districts where the community and workers have weak immunity and are more susceptible to infections, the use of District Mineral Funds (DMFs) for providing health care must be sanctioned 30

• Direct Cash Transfer: The Scheduled Tribes are India’s poo rest people, with five of 10 falling in the lowest wealth bracket, according to the 2015 -2016 National Family Health Survey (NFHS -4). Experts suggest that direct cash transfers to the poorest especially the labourers who have lost their livelihood due to the lockdown must be considered. There are emerging concerns about direct benefit transfer (DBT), based on the Ja n Dhan- Aadhaar-Mobile (JAM) architecture, which allows direct transfer of government -sanctioned welfare funds to bank accounts of the beneficiar ies as many people in rural areas, particularly migrant labourers, do not have bank accounts.In such cases, clear directions by the finance ministry is required to b e able to transfer relief funds 31. The MSP scheme of the Union Govt. for marketing of MFP s has an outlay of Rs. 60 crore between 2016-1932, the states also have their kitty which is la rgely lying unused. In mining affected districts the underutilized DMF funds should also be released for direct cash transfers for at least the next 3 months. Sta te Governments must ensure

that the cash transfers recently announced by the central government reach the community, especially , widows, elders and persons with disability (PwD).• Proper implementation of universal PDS:The lack of wages and income will eventually push lakhs of tribals into poverty and hunger. There is a huge shortage of food and essential items in these areas . As suggested by many experts and economists, the excess food stocks of the Food Corporation of India (F CI) must be released, transported and made available to the poor families across the country. Clear guidelines must be given to the district administration for universal PDS distribution for at least 6 months with speci al emphasis on these categories -BPL, Persons with Disability (PWD),

Aged (Annapurna) and Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs). While rice is being provided , the PDS also needs to expand the nature of items under it to meet sanitation and food security needs in these areas and include rice/ wheat, sugar, sal t and spices, pulses, edible oi l, washing soap and detergent • Ensuring MGNREGA wages/ jobs and in absence of jobs, minimum wages: Government has opened up MGNREGA work recently. While the government in its notification on 15 April did announce that all pe nding MGNREGA wages should be disbursed by April 10, this has not yet happened. The Finance Ministers’ announcement of providing an average of 2000 rupees extra per household through MGNREGA is not really an increment but just an inflation adjusted rate 33. What is needed now is immediate sanctioning of work, release of pending payments, advance payment of wages for at least 50 days of work and increasing th e number of days of work beyond 100 days in all fifth schedule V areas . Given the situation of rural distress with large number of returning migrants many more collective and individual work needs to be opened under MNREGA such as community forest management plantations, preparing nurseries, prot ection and management of Community Forest Rights areas .

• Withdraw regressive policies issued by MOEFCC: For one, the advisory that restricts co mmunity’s access to protected areas to avoid transmission of the virus to the animals without any scientific basis wi ll severely threaten the lives and livelihood of forest dependent communities. This must be withdrawn immediatel y. Second, the regressive Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) draft notification that provides for a reduction of time period from 30 days to 20 days for the public to submit their responses during a p ublic hearing for any application seeking environmental clearance. The current notification, if it comes into force, is a move towards seeking investment irrespective of any adverse environmental consequences that cou ld follow. This notification would need more debate and discussion with s takeholders and needs to be initiated once the situation normalizes. For now, it should be withdrawn immediately.

• Supporting Agriculture and creating livelihoods as a part of a long term solution: It is important that the small landholders who have individual forest rights title (IFR) are provided free seeds and fertilizers to ensure food security and livelihood with dignity.