Study paper prepared by: Dr. Hariswar Dayal and Bharti

AbstractThis paper attempts to understand the effect of the COVID-19 shock on the labour market in Jharkhand by examining the vulnerabilities of the workforce using mainly the data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (2017-18), CMIE’s Consumer Pyramid Household Survey (CPHS), census 2011 and some micro studies. Only 23.41 % of the workforces of the state are occupied in Regular Salaried occupations which offer them security of employment and salary. A very small proportion of these workers has an activity contract of more than three years and has access to social security benefits and government managed employees provident fund scheme. Thus, a lopsidedly huge portion of the workforce is confronting occupation and income misfortunes as an outcome of the pandemic and lockdown. This paper also looks at the disparity in trouble faced by urban and rural Jharkhand and has also discusses the vulnerability of women. To look at the trends and patterns in LFPR and unemployment rate we used Consumer Pyramid Household Survey of CMIE and found out that the incidence of unemployment (particularly in the age group of 19-29 among both males and females) in Jharkhand is high, which kept on increasing after lockdown and peaked in May 2020. We have classified industries (utilizing NIC 2008) into Priority and Non-Priority as indicated by the MHA guidelines during Lockdown and then attempted to quantify probable shock in the labour market utilizing PLFS 2017-18 and taking the population projections of 2011 census as multiplier. Our finding suggests that that like the rest of the country we are likely to see increasing inequality in the state’s labour market - between workers who have a steady source of income, some degree of social security, and are engaged in sectors that are more amenable to shifting their activities online and those who are deprived of them.

GlossaryWorkers (or employed): Persons who, during the reference period, are engaged in any economic activity or who, despite their attachment to economic activity, have temporarily abstained from work for reasons of illness, injury or other physical disability, bad weather, festivals, social or religious functions or other contingencies constitute workers. Unpaid helpers who assist in the operation of an economic activity in the household farm or non-farm activities are also considered as workers. All the workers are assigned one of the detailed activity statuses under the broad activity category 'working or being engaged in economic activity'.

Seeking or available for work but have failed to do work (or unemployed): Persons, who, during the reference period, owing to lack of work, had not worked but either sought work through employment exchanges, intermediaries, friends or relatives or by making applications to prospective employers or expressed their willingness or availability for work under the prevailing condition of work and remuneration are considered as those who are ‘seeking or available for work’ but without work (or unemployed).

Labour force: Persons who are either 'working' (or employed) or 'seeking or available for work' (or unemployed) during the reference period together constitute the labour force.

Out of labour force: Persons who are neither 'working' and at the same time nor 'seeking or available for work' for various reasons during the reference period are considered to be 'out of labour force'. The persons under this category are students, those engaged in domestic duties, renters, and pensioners, recipients of remittances, those living on alms, infirm or disabled persons, too young or too old persons, prostitutes, etc. and casual labourers not working due to sickness.

Self-employed: Persons who operate their own farm or non-farm enterprises or are engaged independently in a profession or trade on own-account or with one or a few partners are deemed to be self-employed in household enterprises. The essential feature of the self-employed is that they have autonomy (i.e., how, where and when to produce) and economic independence (i.e., market, scale of operation and money) for carrying out their operation. The remuneration of the self-employed consists of a non-separable combination of two parts: a reward for their labour and profit of their enterprise. The combined remuneration is given by the revenue from sale of output produced by self-employed persons minus the cost of purchased inputs in production.

The self-employed persons may again be categorized into the following three groups:

- own-account workers: They are the self-employed who operate their enterprises on their own account or with one or a few partners and who during the reference period by and large, run their enterprise without hiring any labour. They may, however, have unpaid helpers to assist them in the activity of the enterprise.

- Employers: The self-employed persons who work on their own account or with one or a few partners and by and large run their enterprise by hiring labour are the employers, and

- Helpers in household enterprise: The helpers are a category of self-employed people mostly family members who keep themselves engaged in their household enterprises, working full or part time and do not receive any regular salary or wages in return for the work performed. They do not run the household enterprise on their own but assist the related person living in the same household in running the household enterprise.

Regular wage/ salaried employee: Persons working in other’s farm or non-farm enterprises (both household and non-household) and getting in return salary or wages on a regular basis (and not on the basis of daily or periodic renewal of work contract) are the regular wage/ salaried employees. This category not only includes persons getting time wage but also persons receiving piece wage or salary and paid apprentices, both full time and part-time.

Casual wage labour: A person casually engaged in other’s farm or non-farm enterprises (both household and non-household) and getting in return wage according to the terms of the daily or periodic work contract is a casual wage labour. Usually, in the rural areas, one category of casual labourers can be seen who normally engage themselves in 'public works' activities.

Current weekly activity status (CWS): The current weekly activity status of a person is the activity status obtaining for a person during a reference period of 7 days preceding the date of survey. It is decided on the basis of a certain priority cum major time criterion. According to the priority criterion, the status of 'working' gets priority over the status of 'not working but seeking or available for work', which in turn gets priority over the status of 'neither working nor available for work'. A person is considered working (or employed)) if he/ she worked for at least one hour on at least one day during the 7 days preceding the date of survey or if he/she had work for at least 1 hour on at least one day during the 7 days preceding the date of the survey but did not do the work.

Public works: ‘Public works’ are those activities which are sponsored by Government or Local Bodies, and which cover local area development works like construction of roads, dams, bunds, digging of ponds, etc., as relief measures, or as an outcome of employment generation schemes under the poverty alleviation programme such as National Rural Employment Guarantee (NREG) works, Sampoorna Grameen Rozgar Yojana (SGRY), National Food for Work Programme (NFFWP), etc.

Usual principal activity status: With the broad activity status identified for a person, detailed activity categories will be assigned on the basis of relatively long time spent on a detailed activity. For example, suppose person A, in the example given above worked in household enterprises without hiring labour for 3 months and worked as casual labour for 2 months, then his usual principal activity status would be, worked in household enterprise (own account worker).

Introduction

The outbreak of corona virus (COVID- 19) has affected both the lives and the livelihoods of the people. It has caused not only a health emergency leading to excessive rise in morbidity, collapse of health care and rising death tolls, but has also disrupted trade, production, mobility of workers, and livelihood of millions of workers around the world. The looming pandemic threatens to hit the developing countries the most, not only in the health insecurity in the short term, but also in causing a devastating social and economic crisis over the months and years to come. Its immediate and ultimate impact on employment, income and production are dependent on the operation of reverse multiplier caused by fall in investment. The fall in investment is expected to be caused by fall in prospective yield of investment because of weakening of domestic and international demand and disruption in supply chain.

Though India’s nationwide lockdown, one of the most stringent in the world, has been relaxed to a large extent, the uncertainly of livelihood, wage loss and lay-offs are likely to linger much longer. The impact of the lockdown and fear of Covid-19 have thrown the product and labour market of the country and its states into great disorder. The production, in most of the units, has either stopped or slowed down. Whatever had been produced has remained unsold. Jobs have been lost, wages and salaries have been reduced or not paid at all, benefits have been withheld, and job security, by and large, has disappeared. The lockdown, thus, has not only caused irreversible damages on the lives of migrant, informal and precarious workers, but has also incited a drop in activities of all sectors, from production to distribution to consumption. In order to insulate the labour markets from the ill effects of lockdown and COVID-19, a soft law approach was executed through an advisory from Ministry of Labour and Employment on 20 March 2020 requiring all employers/ establishments not to terminate employees and not to cut wages. The effect of such advisory, however, is unverifiable and doubtful.

As occurs with all the economic shocks, the worst hit of this pandemic are also the poor, the return migrants, the rural population, the minorities and other socially disadvantaged groups, including women. The results of a survey conducted in 12 states of the country reveal that Muslims experienced substantially larger losses in employment than the Hindus. While job losses have been of similar magnitude in urban and rural India, the uncertainty of getting back to employment is much worse in urban areas. Women and migrant workers fear the worst about the future. Even before the pandemic hit, the trend in unemployment was deteriorating. Surprisingly, those with higher education within the age group of 15-29 suffered higher rates of unemployment. Since the growth of white-collar jobs has declined, the emphasis of the government has been on promoting start-ups to absorb the educated youth. But, the start-ups too have shrunk leaving the educated youth to face the labour market turmoil.

As per the evidences available about Indian labour market segmentation, a very small percentage of workers are employed formally. Most of the workers are engaged in informal sector. They are self-employment or engaged in precarious jobs without any rights, social security or other benefits. Only about 10 per cent of the workers are employed in work where they enjoy social security.

Many informal workers are engaged in micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) producing intermediate inputs and services for other sectors. This sector has suffered a lot because of COVID-19. As a result, the workers of this sector have suffered wage loss or salary cut during lockdown and in the ensuing months. Very few of the workers of this sector are in a position to work from home. Retail and manufacturing jobs require physical presence, so during the lockdown workers of these sectors were badly affected. Even after the lockdown, this sector has failed to regain fully because of the fear of the people and the need and requirement to maintain social distance. Therefore, income for the workers who are unable to work remotely has fallen faster than those who are able to work from home. In order to ameliorate the condition of those who lost their jobs or experienced loss in income/wages/salary and social security benefits, three pronged strategies are required; the promotion of the labour intensive economic activities on a priority basis, improvement in market condition including the supply chain for the products and services of self employed and formalization of employment contract for the wage and salaried workers.

COVID-19, Lockdown and Income and Employment Loss

The COVID-19 and the lockdowns imposed across countries as containment measures has resulted in halting of almost all economic activities in most economies across the world. It has been described as the biggest global economic crisis since the Great Depression (World Bank, 2020). The World Bank forecasts that the global gross domestic product (GDP) will contract by 5.2 per cent in 2020. This could potentially result in an increase in global poverty for the first time since 1990, pushing 60 to 100 million people into poverty (Lakner et. al., 2020; World Bank, 2020). Other researchers have also predicted that in the worst-case scenario about half a billion people might be pushed into poverty (Sumner et. al., 2020) and more than 300 million full-time jobs are expected to be lost worldwide in the second quarter of 2020 (International Labour Organization, 2020).

The complete lockdown imposed by the India government in response to the pandemic lasted almost two months and was among the most stringent in the world (Hale et.al. 2020). The first lockdown was announced on March 24th, and was to last until April 14th. It was later extended till May 3rd which was further extended to May 18th. During this period, all travel, schools, colleges, large gatherings and almost all economic activity other than a few essential services were prohibited. The lockdown has been gradually relaxed, but restriction on some of the activities still persists.

The strict lockdown has resulted in large scale economic distress and food insecurity as large sections of the population subsist on daily earnings without any savings to tide them over the halt in economic activity (Ray and Subramanaian, 2020). The first nine weeks of the lockdown has been estimated to cost approximately ₹ 23 trillion (11.5 percent of GDP). The GDP of the country contracted by 23.9 percent in the first quarter of this financial year and is predicted to contract by anywhere between 5 to 12.5 per cent in 2020-21 (Sen, 2020). This fall in GDP has both been the cause and the result of loss of job and income of a large number of people.

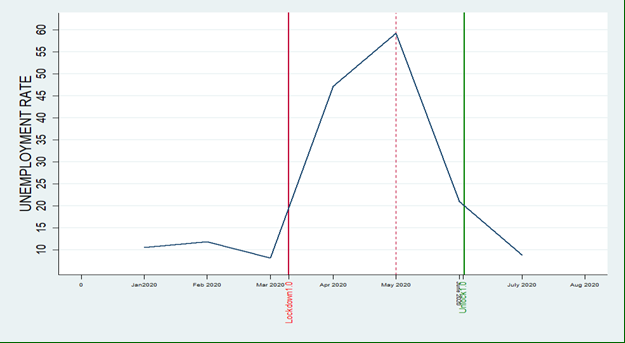

Figure 1 : Unemployment Rate in Jharkhand from January 2020 to July 2020

Unemployment in Jharkhand and India

As discussed above, the COVID-19 and the ensuing lockdown has caused job and income loss for a large number of people in Jharkhand. Unemployment in Jharkhand, which usually used to be less than the national average, remained higher than the national average and than most of the states of the country during the lockdown and in the following months. As per the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), in March 2020 the unemployment rate in Jharkhand was 8.2 per cent, less than that of the all India average of 8.8 per cent but between April and September 2020 it remained more than the all India average. The unemployment in Jharkhand jumped to 47.1 per cent in April 2020 and 59.2 per cent in May 2020 – during the peak of the lockdown. The unemployment at the all India level was also high in these two months but was less than half of that of Jharkhand. The unemployment in the state started decreasing with the relaxation of the lockdown. After the unlock-one, the unemployment in Jharkhand decreased to 20.9 per cent and that of India was 10.2 per cent in June 2020. Since then the unemployment rates, both at the state and national level has remained in single digit, but the state unemployment in state has remained more than the national level (see table 1 below).

| March | April | May | June | July | August | September | |

| Jharkhand | 8.2 | 47.1 | 59.2 | 20.9 | 7.6 | 9.8 | 8.2 |

| All India | 8.8 | 23.5 | 21.7 | 10.2 | 7.4 | 8.3 | 6.7 |

The unemployment during normal times uses to be low among poor and high among the economically well offs. This is because the poor cannot afford to remain unemployed and get engaged in whichever job comes in their hand even if it is undignified; the well offs, on the other hand, wait for dignified and well-paid job opportunities. As a result, unemployment, during normal times, used to be low in low income states. During pandemic, however, the opportunities for even less dignified or undignified jobs have shrunken, causing increase in unemployment among the poor and deprived. This is the reason for prevalence of high unemployment in a poor state like Jharkhand.

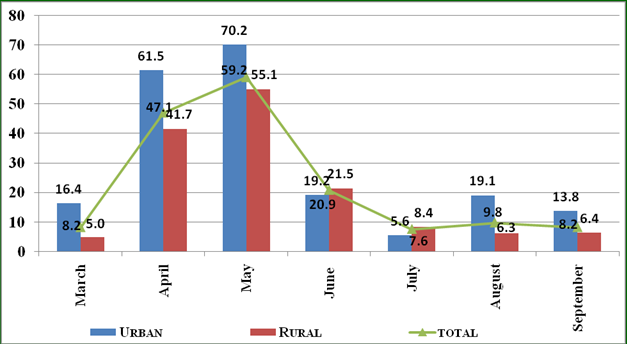

Unemployment in Rural and Urban Areas of JharkhandThe unemployment in urban area was more than that in the rural areas of Jharkhand between March and May, 2020. This usually is the case during agriculturally lean season, when a large number of labourers, in absence of sufficient work opportunities in the villages, migrate from the rural areas of state to urban areas. In the month of April and May 2020, both the rural and urban unemployment increased, but the rural unemployment increased faster than the urban unemployment, causing an increase in the gap between the rural and urban unemployment. This happened because, in absence of work during the lockdown, some of the migrant workers returned to their homes during these two months. The unemployment in both the rural and urban areas decreased in June and July with the relaxation of lockdown and resumption of some of the economic activities. It decreased at a faster rate in urban areas than in the rural areas. June and July are agriculturally busy season for the state. In expectation of getting engagement in Kharif sowing and other related works, many labourers came back to their villages. Some of them went back urban areas after the busy agricultural operations, causing a reversal of the trend.

Figure 2 : Unemployment in rural, urban Jharkhand between March and September 2020

Source: CMIE,

https://unemploymentinindia.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=wsttimeseries&index_code=050050000000

Employment and Income Loss in Rural Areas

In the survey conducted by Azim Premji University (APU study) , 58 per cent of the respondents of the rural areas of the state reported that they lost their job in this period. Casual wage workers were the worst hit - 76 per cent of them lost their jobs. The casual workers and self employed non agricultural workers reported 65 per cent fall in their average earnings in this period.

The farmers were also badly hit by the lockdown. Agriculture sector though not impacted due to good weather condition but was severely impacted due to disruption of supply chain and transportation. 89 per cent of the farmers reported that they were unable to sell their produce at full prices. Salaried wage workers were also affected very badly; 42 per cent of the salaried wage workers also reported that they were either not paid their salaries or were paid only reduced salaries.

As a result fall in employment and income 27 per cent of the households reported that they did not have enough money to buy even a week’s worth of essentials and 77 per cent of the households reported consuming less food than before.

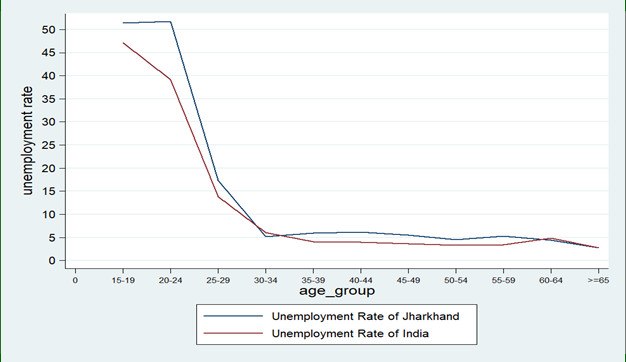

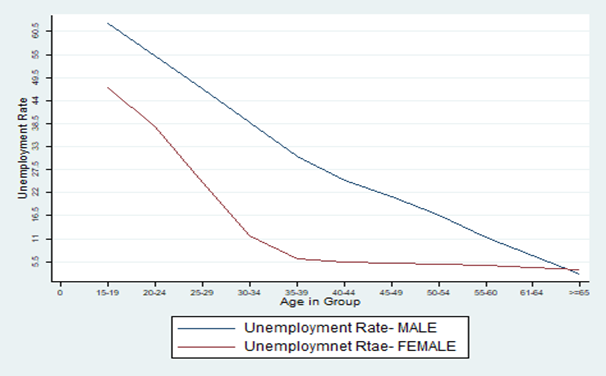

Unemployment by Age groupUsing Consumer Pyramid Household Survey of CMIE we have drawn the unemployment rate from January to April in Jharkhand and in India among different age group. Unemployment Rate is high is for age group of 15 to 19 both in Jharkhand and in India. It decreases with increase in age till the age of 30 and then remains almost same till the age group 60 to 64. This is because those in the lower age group wait for longer period in search for decent employment while with increase in age people start becoming desperate for employment and therefore take up whatever opportunity comes before them. Unemployment Rate is high is higher in Jharkhand than in India in all age groups. The difference between the unemployment rate of Jharkhand and India is higher in lower age group, especially in the age group of 15 to 30, than in the higher age group (see fig 3.).

The migrant, casual and contract workers, the self employed engaged in low productive works and those involved in unorganized sector have been most harshly hit by it.

Figure 3 : Unemployment Rate in Jharkhand and India in Jan- April 2020

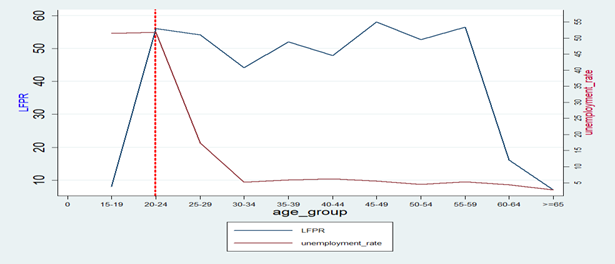

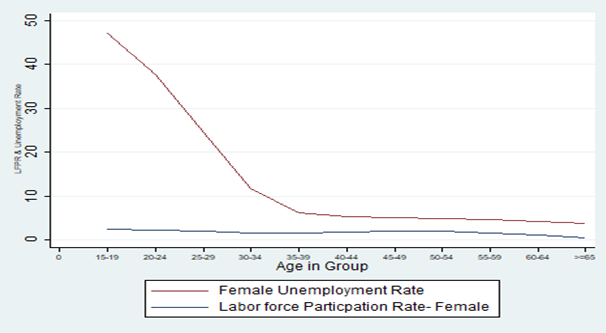

People who are in age group of 15-19 have a very high rate of labour force participation. Fig 4 shows both the Labour Force participation Rate (LFPR) and Unemployment Rate are high among the Youth. The intersection of the LFPR curve and Unemployment curve in the figure below show that very few in the age group 19 to 24 them are employed. As discussed above, the possible explanation of higher labour force accompanied by higher unemployment in the age group of 15-24 is less desperation for employment and higher capacity to wait for a decent job among youth.

There is a steep decline in the unemployment rate from the age group of 20-24 to 25-29. There is further decline in unemployment rate in the higher age group than in the age group between 20-24 and 25-29 and between 25-29 and 30-34.

Figure 4 : LFPR and Unemployment Rate in Jharkhand (Jan- April 2020)

Workforce of Jharkhand in Jeopardy

For examining the vulnerability of workforce of Jharkhand we need to understand the structure of the state’s workforce. We have attempted to do so using the unit level data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2017-18.

- We first need to know the nature of employment arrangements and whether workers in different employment arrangements have access to social security and/or written contracts.

- And second we need to study the sectoral composition of employment. Studying sectoral composition is very important and crucial as COVID-19 and lockdown has affected the occupations asymmetrically.

Approximately 43 per cent of the workers are self employed as own account worker and as employer, 23.41 per cent of workers are regular salaried/wage (RWS) employee and 21.5% of workers worked as casual wage labour according to PLFS in 2017-18. Moreover, the majority of these labourers of Jharkhand were occupied with such activities where work from home is not possible. RWS workers receive salary on regular basis and not on the basic of daily or periodic renewal of work

contract. RWS workers have some degree of income stability, which makes them better off than casual workers; they too do not always have access to social security benefits or secure job contracts. About 44% of Regular Salaried workers (RWS) do not have any social security benefit (Provident Fund / pension, gratuity, health care & maternity benefits). The proportion of RWS workers who had access to at least one social security benefit and therefore a minimal degree of social protection was very low. Thus, very small proportion of workforce had jobs which offered them any conceivable level of assurance of protection and would therefore fit the criteria of what is called a decent earning job to lead a decent living. So it is important to bear in the mind that the crisis due to COVID-19 has come in the backdrop of pre-existing unemployment and a high proportion of workforce which is very vulnerable due to almost absence of security and regular wages and salary.

In addition to access to social security benefits, another parameter that enables us to understand the vulnerability of RWS workers is the degree of job security their contract offers. Here too, the outcomes are disappointing. In 2017-18, the share of RWS workers who had no job contract was as high as 64.9%.

Further, we have examined employment arrangements by the degree of social security benefits they offer and the security of tenure in Jharkhand (Table 2). Here we find that amongst those who had no written job contracts, 74.9% had access to no social security benefits. On the other hand, amongst those who had written contracts of more than 3 years, only 8.7% did not avail any social security benefits. Arguably, such workers who have long term relationship with the firm and are likely to have acquired firm specific skills, have a lower probability of being laid off compared to other workers. The percentage of such jobs is low and has fluctuated between 2% and 3% of total employment over the last few employment-unemployment surveys (2004-05, 2011-12 and 2017-18). These surveys, therefore, reiterates that, job security is a privilege for a limited few in India. It also suggests that the oft-cited statistic of 90% of India’s workforce being in informal employment underestimates the true extent of vulnerability of the workforce as it is based on a fairly relaxed definition of what comprises a formal job.

Table 2: Distribution of RWS Workers by Type of Contract and Access to Social Security Benefits| Eligibility of Social Security Benefits | No written job contract | Written job contract: for 1 year or less | Written job contract: more than 1 year to 3 years | Written job contract: more than 3 years | Missing /not applicable | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible for: only PF/ pension (i.e., GPF, CPF, PPF, pension, etc.) | 5.74 | 34.88 | 23.33 | 31.65 | 0.00 | 10.71 |

| Only gratuity | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| Only health care & maternity benefits | 0.00 | 2.33 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| Only PF/pension & gratuity | 1.83 | 2.33 | 0.00 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 1.67 |

| Only PF/ pension and health care & maternity benefits | 1.41 | 2.33 | 6.67 | 1.38 | 0.00 | 1.54 |

| Only gratuity, health care & maternity benefits | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 0.27 |

| PF/ pension, gratuity, health care & maternity benefits | 7.65 | 6.98 | 30.00 | 53.67 | 0.00 | 14.79 |

| Not eligible for any of above social security benefits | 74.90 | 37.21 | 36.67 | 8.72 | 0.00 | 63.39 |

| Not known | 8.23 | 13.95 | 3.33 | 2.29 | 0.00 | 7.43 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 100 |

Given the extent of precocity and lack of security of tenure across work arrangements, it is unsurprising that the period during the national lockdown would have witnessed substantial job losses. These losses might not have been restricted to casual workers only, but also to those RWS workers who have little or no security of tenure. It is therefore unsurprising that the Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS) of CMIE estimated job losses of 122 million in April 2020 compared to the average employment figure of 404 million during 2019-20. While small traders, hawkers and daily wage earning labourers accounted for most of this loss (90 million), the count of salaried employees too fell during this period by 18 million. The financial inability of households to cope with the ongoing economic distress is also evident from the already discussed findings of survey conducted by Azim Premji University.

Data from the PLFS shows that 46.08 % of RWS workers earned below ₹9750 per month (or ₹375 per day), an amount recommended as a national minimum wage by an Expert Committee appointed by the Government of India (January 2019). On the other hand, the share of RWS workers who earned ₹15000 and above was 41.4% (PLFS 2017-18). For casual workers, the share of those earning below ₹375 a day was even higher at 92.5%. Their financial vulnerability is exacerbated by the fact that they are unlikely to get work on every day of the month, and therefore not likely to earn a bare minimum amount for the month. A sudden loss of income for those who have such low levels of earnings and often do not earn even a minimum wage is likely to be devastating. Already wage of workers is very low in Jharkhand as compared to India’s Average. Although, the reliability of data on gross earnings of self-employed cannot be guaranteed as there may be instances of under-reporting, it is not unreasonable to assume that their earnings are low given that over 95% of self-employed are own account workers or unpaid family workers. The latter, in particular, draw from earnings of household enterprises and as earnings drop during a crisis, the pool of household resources dwindles pushing many self employed into margins of subsistence. In this backdrop it is unsurprising that ILO (2020) estimates that in India about 400 million workers in the informal economy are at risk of falling deeper into poverty.

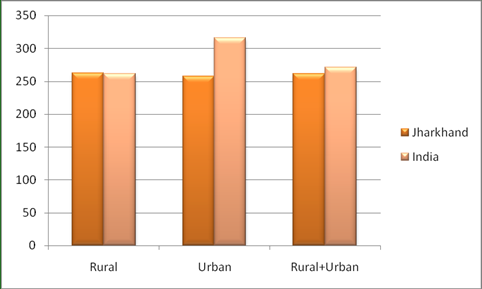

Figure below (Fig 5) shows that Average wage earnings per day from causal labour work other than public work (in currently weekly status) in Jharkhand are less than India. In this backdrop it is unsurprising that ILO (2020) estimates that in India about 400 million workers in the informal economy are at risk of falling deeper into poverty.

Figure 5: Average wage earnings per day from causal labour work other than public work

(in currently weekly status) in Jharkhand and India (Rural and Urban)

While economic activity has halted across almost all sectors as a consequence of the COVID-19 crisis, some sectors have been more severely impacted than others. ILO (2020) has classified sectors on the basis of their susceptibility to the ongoing crisis (Table 3 reports this classification). Outside of the agricultural sector, which accounts for the largest share of total employment, three key sectors-manufacturing, construction and trade, hotels and restaurants (each of which account for 4.99% of total employment) have borne a significant brunt of the COVID-19 shock.

Table 3: Sectoral breakdown of Employment by Employment Status| ILO classification of risk to output | Sectors | Share of employment in total employment | Casual | RWS | Self Employed |

| Low to medium | Agriculture | 36.39 | 4.08 | 0.32 | 68 |

| Medium | Mining & Quarrying | 2.01 | 13.04 | 86.95 | 0 |

| High | Manufacturing | 23.09 | 130 | 243 | 362 |

| Low Electricity | Gas & Water Supply | 0.76 | 7.6 | 69.2 | 19.2 |

| Medium | Construction | 15.52 | 85.17 | 2.62 | 12.2 |

| High | Trade, Hotel & Restaurants | 4.99 | 18.17 | 26.9 | 45.6 |

| Medium-High Transport, | Storage & Communication | 5.53 | 19.5 | 52.6 | 26.3 |

| Medium-High Finance, Business, Real Estate | 1.1 | 4.8 | 59.5 | 34.14 | |

| Low | Public Administration,Health, education | 10.53 | 3.03 | 80.9 | 15.7 |

To begin with, we look at the agricultural sector. Although the ILO’s framework places this sector in the low to medium risk category with respect to COVID-19, there are few issues that need to be highlighted in the Indian context. Initially, the circumstances of the lockdown coincided with the harvest season, when demand for labour is at its peak for harvesting and post-harvesting operations. The mobility restrictions at the time of harvest created shortages of farm labour to perform these operations. Furthermore, because of transportation bottlenecks, farmers confronted challenges getting their produce to the market. This has been particularly challenging for cultivators of perishable produce who had to destroy their crops in certain instances. In other instances, farmers who were able to sell their crop did not receive the desired price for their produce . As a result of these factors, farmers' incomes must have been affected harshly and they have to battle to recoup the costs they have incurred in the Rabi season. It may adversely affect their farm level investment in the current agricultural (Kharif) season. It is important that agrarian pain has been fermenting in the Indian economy for some time and the rural wages and other payments have stayed languid since 2014-15 (Himanshu, 2019). COVID-19 is intensifying this crisis further. What is more, many of the migrants who have lost their jobs in urban areas and returned to their villages are likely to resort to work in the agricultural sector and the sector, which acts as an ‘employer of last resort’ will not be able to absorb them all at remunerative wage.

Next, we turn to the manufacturing sector which has been hit by multiple shocks concomitantly (Baldwin, 2020). The first shock came from containment measures as factories were closed. The second shock to the sector has come from disruptions in global supply chains which have hindered access to imported inputs. India’s manufacturing sector has a high dependence on imported inputs and this dependence has in fact increased over time (Ghose, 2016). The third shock is in form of availability of labour force. With the exodus of migrant labour from cities, factories are also likely to face labour shortages in the immediate term. The fourth shock is probably going to originate from shortage of demand. As employment misfortunes mount and income lessen, the demand for merchandise is probably going to decrease. This is especially valid for less essential products, for example, cars, clothing and footwear which are non-essential in nature and whose demand can be effortlessly deferred. A large number of those involved in production, assembling and distribution and sale are going to be adversely affected. A large number of the workers engaged in their production and distribution are susceptible to be retrenched.

The construction sector emerged as an important source of employment generation in India between 1999-2000 and 2011-12, growing annually at over 9% (Mahajan & Nagaraj, 2017). The employment boom in construction was largely a rural phenomenon. While employment in rural construction grew at 12% per annum, that in urban construction grew at only 5% per annum. The expansion for rural construction (in particular rural private residential construction) in this period was mainly because of rise in rural wages and fall in real price of cement. In Jharkhand also the employment in construction sector grew at a fast rate in this period. However, in the period after 2011-12, the share of employment in construction has remained sluggish at approximately 15.52% in Jharkhand. The tepid contribution of this sector to employment after 2011-12 is not just a consequence of the financial difficulties faced by it in the wake of the National Banking Financial Crisis, but also because of the sluggish growth of rural wages since 2014-2015. For a sector that is already under stress, the pandemic and lockdown are likely to worsen the matter. The sector will struggle to resume activity as it grapples with supply chain disruptions, labour shortages due to unavailability of migrant workers and sharp decline in income and therefore demand. Given the close proximity in which construction workers work at the worksite (and often even live), the chances of resumption of this activity is low because of the recommended social distancing norm.

Another badly affected sector is the trade, hotels and restaurants segment. Some workers in this sector are engaged in essential activities and may continue to work, despite facing greater occupational health risks (ILO, 2020). Most other workers are engaged in non-essential businesses which are facing widespread closures and are likely to face sharp reductions in employment. What is more, even as lockdown restrictions are relaxed, restaurants, hotels and brick and mortal retail units may not see an uptick in demand till a vaccine is developed for the Corona Virus. Given that a mere 4.7% of workers in this sector fall in the category of regular formal employment, with a disproportionately large share in low paid and unprotected jobs, we can expect to see widespread layoffs as employers grapple with COVID-19 induced uncertainty. The importance of this sector as a source of employment generation is likely to diminish in the near future. Similarly, the transport, storage and communication industry which accounts for about 6% of total employment is likely to be severely impacted by the COVID-19 shock. As passengers travel less, the transportation industry, road, rail and air is likely to suffer. This will affect in turn several other sectors closely related to them. A large number of workers in the transport industry, in particular air transport are likely to witness large scale job losses. On the other hand, demand for drivers, postal and other delivery workers, as well as people who work in warehouses may rise to meet the increased demand for online retail.

In contrast to the above sectors, services such as public administration, health and education are relatively low risk in terms of job losses. Health workers are high in demand and the sector is likely to witness significant expansion as governments are pushed to spend on healthcare in the face of a public health crisis. Education activities are more amenable to being moved online. A large number of employees in these sectors are in regular formal jobs which offer some degree of social security, and are better placed to cope with the ongoing crisis. About 75% of workers are in the category of RWS workers, with a mere 4% in casual employment. Another sector which is marked by a fairly high share of regular salaried workers (59.5%) is the finance, business and real estate services. Although this sector is classified as having a medium to high risk, the relatively low share of workers in informal work arrangements and the ability to move work online, makes workers in this sector less vulnerable. Also, earnings of workers in this sector are higher than those in low-end services, making them better placed to deal with the crisis financially.

The above facts suggest that the first order effects of the COVID-19 shock have been particularly severe for sectors which account for the lion’s share of employment (80%) i.e. agriculture, manufacturing, construction and trade, hotels and restaurants. Importantly, these sectors are an important source of employment for the less educated. For instance, over 90% of workers in construction have less than of up to secondary level education. In the manufacturing sector and the trade, hotels and restaurants sector the corresponding statistics stood at 76% and 70% respectively. We have also discussed above that these sectors are dominated by informal and precarious work arrangements (Table 2). In contrast, the high end service sectors, which are relatively less affected than the above-mentioned sectors by the COVID-19 shock, employ more educated workers and have a higher share of regular protected employment. However, their contribution to total employment is low.The differential impact of the COVID-19 crisis on workers depending on the nature of employment arrangement and sector of employment suggests that we are likely to see increasing inequality in India’s labour markets between workers who have a steady source of income, some degree of social security, and are engaged in sectors that are more amenable to shifting their activities online and those who are not. It is also worth noting that the most secure jobs are typically held by the more educated. It is the relatively less educated, unskilled and low skilled workers who have a high probability of being rendered unemployed and losing livelihoods due to the sectoral profile of their employment and nature of work arrangement. They stand to bear a disproportionate brunt of the COVID-19 shock.

Vulnerability of Women Workforce in Jharkhand:

Events like poverty, war, natural disaster or disease outbreaks, have usually altered the power relations between women and men. Some authors suggest that gender-mainstreaming activities in the context of disaster may be empowering for women, particularly for those women who acquire new opportunities, while some other scholars feel that the burden of new roles and responsibilities fall on women during any disaster without the alleviation of any of the existing responsibilities (Helen Jaqueline McLaren et. all, 2020). The shock of COVID-19 has increased deprivation of women. On one hand it has caused increase in their unemployment and on the other the vulnerability to infection and disease of those who are employed. Some of the women dominated jobs have greater risk of COVID infection. Nursing, for example, carries risks due to an increased exposure to airborne or physical contacts. They do not have the capacity to avoid Covid-19 exposure and are unable to socially distance or self-isolate. Approx three dozen staffs of the RIMS gynaecology department, all women, were exposed to corona virus infection and over 60 health workers of the same department on April 26th found themselves COVID positive.

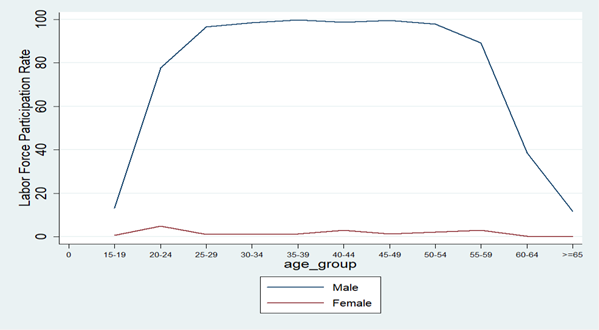

Low Labour Force Participation Rate among Females: Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) of women in Jharkhand is much less than that of the males. According to PLFS 2017-18, in Jharkhand, the LFPR of Females was 8.7 against 50.3% of that of the Males. This is an indication of preponderance of women in unpaid and unrecognised family work on one hand and lack of economic independence of women on the other.

Utilizing the Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS) of CMIE between Jan – April 2020, we ran Local Polynomial Regression to see the Labour Force Participation Rates (LFPR) of Male and Female among various age groups. As discussed above, the LFPR of Female is far less than that of Male. Gap is their participation rate is highest in the age group of 29 to 50. Also convergences of curve at later age shows that even Male are not in Labour Force in substantial number beyond the age 55. The low LFPR among women explains prevalence of low unemployment among them. Unemployment Rate among Male is higher than that of the females.

Fig gives us additionally understanding with respect to the weakness of ladies which shows that there is exceptionally high pace of joblessness among female at the age of 15-30. Because of variables like low expertise, scholastic attainment, culture norms, neighborhood impact this high pace of joblessness is common.

Figure 6 LFPR of Male and Female in Jharkhand among different age groups

Figure 7: Unemployment Rate among Male and Female in Jharkhand

Figure 8 : Unemployment Rate and LFPR of female in Jharkhand

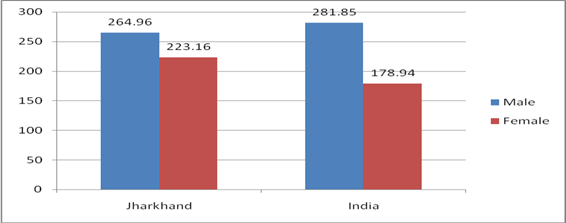

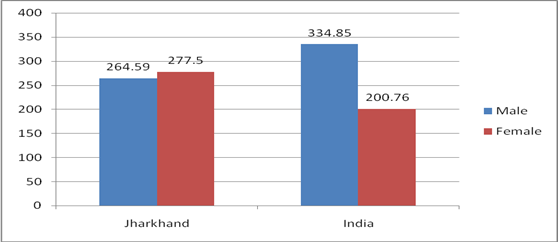

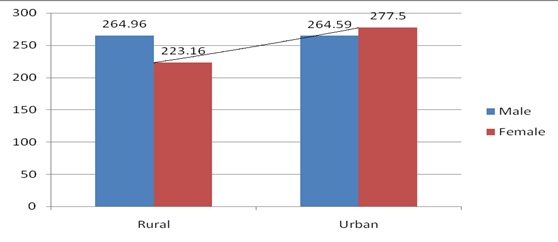

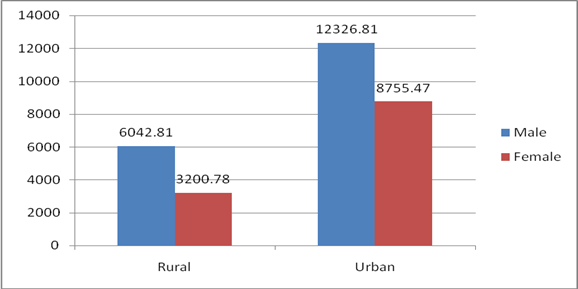

Those women who are employed are paid less than their male counterparts. Figure 9, 10 and 11 show the disparity in Average wage earnings per day from causal labour work other than public work among male and female (it has been calculated from PLFS 2017-18 in Currently Weekly Status employment). In Jharkhand, the average wage of females in such types of work is 18.7 per cent less than that of the males. The magnitude of discrimination against women in Jharkhand is, however, less than that at the all India level. At all India, the average wage of females is about 57 per cent less than that of the males. The gender wage gap in Urban India is more than Rural India but in Jharkhand the condition is just the reverse. In Jharkhand, the average wage of female workers, in such types of work is more than that of the males. As a result, in Jharkhand, the gender gap in average wage in rural area is more than in the urban areas, so there are many instances where women from rural area come to urban areas to work as casual workers, especially in construction sector. Due to COVID-19 and lockdown most of these activities are in standstill condition. As a result, the women must have been hit with a hefty thwack.

Figure 9 : Average wage earnings per day from causal labour work other than public work (in current weekly status) in Rural Jharkhand and Rural India for Male and Female

Figure 10: Average wage earnings per day from causal labour work other than public work (in currently weekly status) in Urban Jharkhand and Urban India for Male and Female

Figure 11: Average wage earnings per day from causal labour work other than public work (in currently weekly status) in Rural Jharkhand and Urban Jharkhand for Male and Female

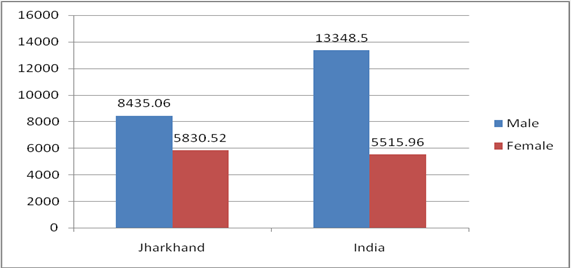

Figure 11: Average wage earnings per day from causal labour work other than public work (in currently weekly status) in Rural Jharkhand and Urban Jharkhand for Male and FemaleThe gender disparity persists in the earnings of self employed also. In Jharkhand, the average monthly gross earnings of the self employed women, calculated from PLFS (in current weekly status), is 44.7 per cent less than their male counter parts. The gender gap in the earnings of self employed is 142 per cent at the all India level.

In Jharkhand, the average monthly gross earnings of the self employed in the rural areas are much less than that in the urban areas, for both the males and females. The gender disparity in average monthly gross earnings of the self employed in the rural areas, however, is much higher than that in the urban areas.

Figure 12 : Average gross earnings during last 30 days from self-employed person (in currently weekly status) in Jharkhand and India for Male and Female

Figure 13 : Average gross earnings during last 30 days from self-employed person (in currently weekly status) in Rural Jharkhand and Urban Jharkhand for Male and Female

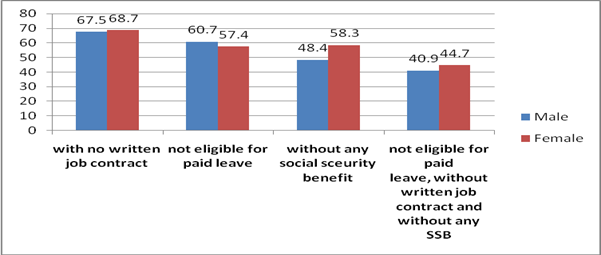

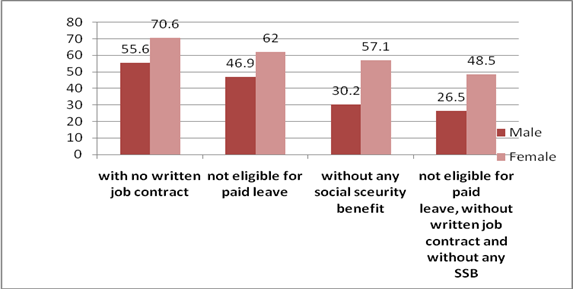

Figure 14 shows the percentage of regular/salaried employees in usual status (ps+ss) in non-agricultural sector (calculated using PLFS 2017-18) in Jharkhand for Male and Female. It shows that a larger proportion of women are exposed to insecurity than the men. About 69 per cent of such women have no written job contracts; about 58 per cent of them do not have access to any social security benefit. It shows the risk of increase in vulnerability of women in lockdown during this pandemic. Since in the rural areas of the state very low proportion of women is in regular salaried class, in comparison to rural areas, a higher proportion of women with very little or no security at all exist in urban areas. About 71 per cent of regular salaried women workers were with no written job contract, 62 per cent of them are not eligible for paid leaves and about 57 per cent of them are without any social security benefit.

Figure 15: Percentage of regular/salaried employees in usual status (ps+ss) in non-agricultural sector in Rural Jharkhand for Male and Female>

Figure 16: Percentage of regular/salaried employees in usual status (ps+ss) in non-agricultural sector in Urban Jharkhand for Male and Female

of Shock in the Labour Market

WE have estimated the shock in the labour market due to imposition of Lockdown in Jharkhand. For this we have used PLFS 2017-18 (the latest data available), NIC 2008 Code which PLFS uses and Census of India 2011. We have assumed that there is no change in the employment structure in 2020 from 2017-18. It seems to be a valid assumption because the employment structure does not change in such a short span of time. We utilize two measurements to assess the shock

- • The principal metric depends on whether a worker is employed in Priority Industry or Non- Priority Industry according to Ministry and Human Affairs guidelines.

- Second we estimate the degree to which a labourer can play out the work exercises at home.

We develop Binary Index for by giving number 0 if the particular industry falls under Non-Priority and 1 if the industry comes under Priority sector. According to our estimates labourers affected mostly are those who work in a Non-priority sector industry and can't work from home. Compared to other countries, India has put in place one of the strictest containment and closure policies in the world, according to the COVID-19: Government Response Stringency Index developed by the researchers at the University of Oxford (see Hale et al., 2020).

Since the latest data available is of 2017-18 and so there can be underestimation of the actual impact so to obtain absolute numbers all the estimates are adjusted to the projected population numbers. We have developed Census Adjusted Multiplier which is the ratio of

Results:

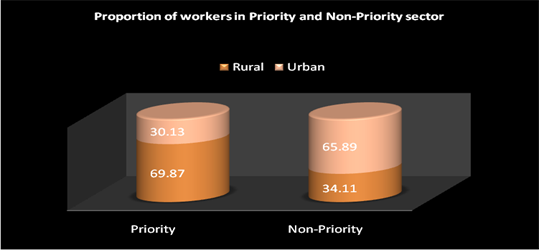

According to our estimates there are only 28.57 per cent of industries (we have used detailed division as per NIC-2008) which falls under the category of Priority and 71.43% of industries are non-essential. We further classified different occupation according to National Occupational Classification 2004 (used by PLFS) and found out that only 26.73% of occupations fall under priority and 73.27 per cent occupations are badly impacted due to lockdown. Adjusting the population of workers (employed in either priority or non-priority activities) to the Census Adjustment Multiplier we find out that there are only 837 workers employed in priority activities and 3977.4 workers employed in non-priority sector.

| Rural | Urban | ||||||

| Priority | Non-Priority | Priority | Non-Priority | ||||

| 42 | 26.58 | 116 | 73.42 | 56 | 30.27 | 129 | 69.73 |

| Total Number of 5-digit NIC Industries in Jharkhand= 343 | |||||||

Figure 17 shows the proportion of workers engaged in priority and non-priority activities during Lockdown in both rural and urban region. We find that in comparison to the rural area, a higher proportion of workers are engaged in non-essential activities in the urban area during lockdown. As government classified most of the agricultural and farming activities as essential and priority, we find a lower proportion of workers employed in non-priority activities in rural areas.

Figure 17: Proportion of workers engaged in essential and non-essential sectors during the lockdown

Some shock in the labour market is absorbed by the workers who could work from home in the lockdown period too. To check the mobility among different work activities and occupation we again gave a binary number to activities; 1 if activities can be performed at home and 0 if the activities cannot be performed at home.

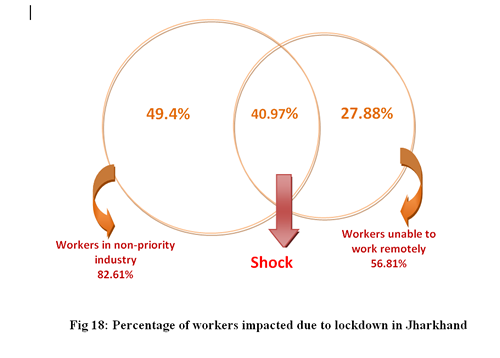

We found out that total per cent of workers who can work from home is 43.19 while 56.81 per cent of workers cannot work from home. Due to provision of work from home shock is absorbed to an extent though not to very high degree and 41% of workers in non-priority sector could work from home.

Policy Recommendation

In order to ameliorate the condition of the workers who have suffered loss of jobs, income and social security five pronged strategies are required; immediate relief in terms of providing employment and income to those who have been worst affected by the pandemic and lockdown, policy for safeguarding the interest of migrant workers, the promotion of the labour intensive economic activities on a priority basis, improvement in market condition including the supply chain for the products and services of self employed and formalization of employment contract for the wage and salaried workers.

Due to COVID 19 pandemic, many individuals lost their employment both in urban and rural area of Jharkhand. As a result, they are facing income and livelihood insecurity and living a precarious life. Those who had migrated to avail better employment opportunities and save some money for their future use, had to return empty handed to their home. They lost their job, income and savings and faced tremendous hardships both at the destination and in their return journey. These people have to be provided with immediate relief so that they can make both ends meet. MGNREGA has provided much needed relief to a large number of labourers in rural areas by providing them work on demand. In line with the Odisha Government, the Jharkhand government must also increase the number of days of employment over and above the stipulated 100 days at least in the most distressed districts.

Unemployment Allowance: MGNREGA has made provision for payment of unemployment allowance to all those labourers who have demanded work but have failed to get it even after 15 days of their submitting application for it. The act says that “if an applicant is not provided employment within fifteen days of receipt of his/her application seeking employment, he/she shall be entitled to a daily unemployment allowance”. However, during lockdown neither the prospective MGNREGA-workers, despite being in dire need for such employment, could demand for work nor could the government provide them employment under this scheme. Such workers must be identified then should be considered for payment of unemployment allowance by the state government. All those who were working as MGNREGA workers just before the lockdown should first be considered for payment of unemployment allowance. The state government, in line with the Odisha government, should ask the central government for approval and financial assistance for payment of unemployment allowance to such workers.

Hike in MGNREGA wages: The wages of the MGNREGA workers have recently been raised by 13.5 per cent from Rs.171 of the last year to Rs. 194 this year. It, however, is 52.5 per cent less than the prevailing minimum wage (Rs. 295.80 per day; Rs. 274.81 basic and Rs. 20.99 as VDA per day) for the unskilled workers of the state. It is also one of the lowest in the country. The MGNREGA wages of only Chattisgarh is less than that of Jharkhand and that of Bihar is equal to that of Jharkhand. For the immediate effect, the state government must increase the wage rate of MGNREGA workers from its own fund at least in the migration prone blocks and districts, where the workers have been worst affected by the pandemic and the districts which have received a very large number of return migrants. For the future it must pressurize the central government to make it equal to the minimum wages of the unskilled workers.

The proposed “Shahri Rojgar Yojna” in the urban areas and newly introduced “PM Garib Kalyan Rojgar Abhiyaan ” in the districts which have experienced very high incidence of return migration (at present three districts of Jharkhand - Giridih, Hazaribag and Godda have been selected for this programme in the first phase) also have the potential to provide immediate relief to a large number of vulnerable workers. The government must monitor these schemes so that they are implemented effectively. The Civil Society Organisations also have equally important role to play. They too should monitor the implementation of these schemes so that these schemes succeed in providing adequate and timely relief to the needy people.

State should take immediate steps to implement Shahri Rojgar Yojna. It should also demand the centre for immediate expansion of PM Garib Kalyan Rojgar Abhiyaan to other districts of the state.

Urban employment (DUET): As suggested by Jean Dreze that government should issue job stamps and distribute them to approved public institutions - schools, colleges , hostels, shelters, jails, museums, municipalities, government departments, health centres, transport corporations, neighbourhood associations, urban local bodies, and so on. These institutions would be free to convert each job stamp into one person-day of work within a specified period, as long as they arrange the work. The wages would be paid by the government directly into the workers’ account on the presentation of job stamps, duly certified by the employer. To avoid collusion, employees would be assigned to employers by an independent placement agency. Some of the work could be organized on a part-time basis—say four hours per day—to make it easier for women to participate. The training component of the scheme—the T in the DUET—would mainly take the form of on-the-job training, as unskilled workers team up with skilled workers. The placement agency, aside from assigning workers to employers, could also play a useful role in skill formation and certification. In principle, a municipality could have multiple placement agencies, some of them organized as workers’ cooperatives. It would be relatively easy to move from DUET towards demand-driven 'employment guarantee'. That would require the municipality to act as a last-resort employer, committed to providing work to all those who are demanding work but not finding any with other approved employers. Alternatively, DUET could become part of a larger employment guarantee programme in urban areas. In deciding on projects, one should give preference to (i) particularly labour-intensive projects, and those that serve (ii) environmental and (iii) health goals. For example, (i) construction projects like building and repairing roads, public housing, etc. (ii) sorting and recycling garbage, refurbishing public spaces and parks in neighbourhoods, building mass transit, fitting solar cells, restoring and cleaning water bodies, rainfall harvesting, and so on (iii) spraying for mosquitoes, covering sewage drains, building public toilets particularly in slums, personnel for primary healthcare centres, hiring more ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) workers, etc. The ‘placement agency’ should be independent and seen to be independent, if the purpose is to minimize collusion. (If it is not a purely administrative body, maybe people nominated by both the ruling party and opposition in the local government should be in the agency).

Every year a large number of workers migrate from the state in search for better employment opportunities. Although, they earn some extra money from migration, they face lots of problem and experience a variety of hardships during their journey to destination, at the place of migration and during their return journey. They are the most vulnerable to all type of unforeseen events, like, accidents, natural calamities, communicable or occupational diseases and epidemic or pandemic. It is the responsibility of the state to safeguard the interest of their residents and to look after their welfare. The state should create an agency within the labour department of the state which will have the records of the migrants, the destinations where they have migrated, the occupation in which they are involved, the agents (if any) through with they have migrated and the employers (if they are not self-employed) with which they are involved. For creation of this data base the panchayat representatives, the labour contractors/agents and the migrant labourers should be contacted. For creating, up-dating and maintaining the records of the migrant workers, they can also be asked for a voluntary registration through a simplified, worker friendly registration system. This agency should be available to the migrant workers through a toll free number in case they require any help. This agency should have links with the agencies/departments concerned with the safety and welfare of the labourers of the states/places where the labourers have migrated. Since the National Capital Region (NCR) is an important destination of the migrant workers of Jharkhand, the office of the resident commissioner of Jharkhand in Delhi can also be assigned to provide support to the migrant workers of this region and of the adjoining areas.

Two of the major problems faced by the migrant workers have been non-portability of the welfare schemes and lack of housing facilities. The central government has promised schemes to take care of these two issues in its Atmanirbhar Bharat package. It has promised for digitalization and portability of PDS cards and entitlements to other welfare schemes. It has also promised for creation of Affordable Rental Housing Complexes (ARHCs) for urban migrants/poor through public-private-partnership. With this scheme, a large part of workforce in manufacturing industries, service providers in hospitality, health, domestic/commercial establishments, construction, Labourers, students etc. who belong to rural areas or small towns and seek opportunities for their betterment will be provided accommodation at affordable rent.

Both the state government and civil societies of the state must pressurize the central government for the speedy implementation of these two schemes and monitor their effective implementation.

Agriculture is one of the most labour intensive activities. It must be promoted through support of appropriate technology, generation and transfer of knowledge (interlinking the lab to the land), infrastructure, especially those related to conservation and use of moisture and provision for proper and remunerative marketing facilities.

Jharkhand has immense potential in field of vegetable and other horticultural products. Facilities must be created for production, storage, packaging, processing and marketing of these products. A large number of workers can be absorbed in these activities.

In order to improve the supply chain of the vegetable and fruit producers so that they get proper price for their products, the Union Government has announced extension of ‘Operation Green’ from TOP (Tomato, Onion and Potato) to all fruits and vegetables (TOTAL) for a period of six months on pilot basis as part of Aatmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan. It aims to provide subsidy of 50 % of the cost of the following two components, subject to the cost norms:

1. Transportation of eligible crops from surplus production cluster to consumption centre.

2. Hiring of appropriate storage facilities for eligible crops (for maximum period of 3 months)

Both the state government and civil societies of the state must monitor their effective implementation. Another labour intensive sector and at the same time one of the most affected sector is MSME (Micro Small & Medium Enterprises). Appropriate measures must be taken to provide support to this sector. Under the Atmanirbhar Abhiyan, central government has announced financial support by facilitating credit and providing loan moratorium to this sector. The state government must make efforts so that this sector succeeds in availing these facilities.

Need for cluster concept: Cluster as a strategy of area-based development particularly for the development of small and micro enterprises is very important. Regional clustering can be used to describe industrial districts of small crafts firms, high technology centers, agglomerations of financial and business service firms in cities, company towns, and large branch plants and their supply chains. Then we need to map the skill and maintain a dynamic registry for the migrants and workers to prepare a database. Appropriate policy measures can be taken for the welfare of migrants. These registries need to be instituted using latest digital technologies along with dynamic unemployment registry. Since the situation is unprecedented, this also provides an unprecedented opportunity for the nation. In the effort to jump-start the economy, mainly the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) sector, we could try and integrate these reluctant-to-return migrant workers into India's rural economy. It is time for the Union ministry of MSME and the state governments to come up with a workable plan to encourage a cluster of the cottage, small and medium enterprises in villages and towns.

The market has been severely hit by the pandemic and accompanying lockdown, the fear of infection, the requirement to follow the social distancing norms and the disruption of the supply chain. This has affected the employment situation in the state, especially the employment of the self-employed workers. In order to improve the employment situation, especially that of the self employed workers market situation must be improved. Efforts should be made to restore the supply chain so that the producers get their inputs without any hindrance and sell their products without any loss. Efforts should also be made to normalise the market under new normal conditions and facilitate marketing of products of the producers especially the products of self employed workers.

As has been discussed above, the workers without proper job contract have been the worst sufferers of this pandemic. A proper job contract, specifying all the duties, privileges and rights of the workers, especially, the Regular Wages and Salaried (RWS) Workers and contract workers must be made mandatory. For addressing to the grievances of the labourers and providing them speedy justice and relief, Grievance Redressal Cells/Forums should be formed in all the districts. The civil society organisations may also be involved in listening, highlighting and redressing the grievances of the workers.

Financing the Employment Providing Strategies

Part of the above mentioned strategies can be financed from the already promised or demanded and expected fund transfer from the centre, another part by using its own fund and the remaining part by expanding its own fiscal space.

- 1. Fund transfer from the centre: In its Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan and in its subsequent announcements the Central Government has promised additional funds to the states to revive the economy hit by the pandemic. These funds can be used to partly finance the above strategies of employment generation. These funds are, however, not sufficient for the regeneration of the economy and for generating enough employment so that most of the unemployed of the state, including those who have lost their jobs because of pandemic, get absorbed. In such cases the state should demand additional fund from the centre to meet its fund requirements.

- Own fund: The state must use it State Disaster Response Fund (SDRF) to provide relief and employment to the return migrants. Government of India has permitted State Governments to utilise State Disaster Response Fund (SDRF) for setting up shelter for migrants and providing them food and water etc. Many of the states are using it for this purpose. Government of Kerala has done exemplary work for the relief and rehabilitation of its return migrants using its State Disaster Response Fund. Besides, SDRF, the state can also use District Mineral Foundation (DMF) fund for creation of additional employment opportunities in mineral producing districts. The government of Odisha is using DMF for increasing the MGNREGA wage and for providing additional employment under MGNREGA. In Keonjhar district of Odisha, Rs. 95 crore of DMF fund is being used to provide additional Rs. 95 per day over and above the centrally decided wage rate and provide 100 days of additional employment over and above the stipulated 100 days of employment in the financial year 2020-21. Keonjhar, thus, has becomes the first and only district in the country to provide minimum wages to all MGNREGA workers, by utilizing the unprecedented opportunity offered by the DMF (The New Indian Express, June 11, 2020).

- Expansion of Fiscal Space: The four ways through which the state government can generate additional resources are (i) increasing the tax rate (ii) improving the tax compliance through better monitoring (iii) reducing the subsidy and (iv) raising public debt. The government has very limited sources of tax revenue. It, however, can generate additional resources by increasing the rates of excise duty on alcohol, which is a sin tax, by revising the circle rates of land and increasing the rates of land registration and the rates of taxes on petroleum and electricity. Similarly, the state can save resources through targeting its subsidies; it can be withdrawn from those who are well off. For increasing the public debt, it should ask the central government to relax the FRBM limits.

Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. 2020. “Unemployment Rate in India” https://unemploymentinindia.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=wshowtab&tabno=0002

Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University.2020. “Azim Premji University COVID-19 Livelihoods Survey” https://cse.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in/ covid19-analysis-of-impact-and-relief-measures/

Dreze, Jean.2020. “The need for a million worksites now” The Hindu, May 25th 2020 https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/the-need-for-a-million-worksites-now/article31665949.eceInternational Labour Organisation.2020. “ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. Second edition”

Lakner et. al., 2020; the impact of COVID-19 (Corona virus) on global poverty: Why Sub-Saharan Africa might be the region hardest hit

Mahajan, K. & Nagaraj, R. (2017). Rural construction Employment Boom during 2000- 12: Evidences from NSSO.

Mclaren, Helen & Wong, Karen & Nguyen, Kieu Nga & Mahamadachchi, Komalee. (2020). Covid-19 and Women’s Triple Burden: Vignettes from Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Vietnam and Australia. Social Sciences. 9. 87. 10.3390/socsci9050087.

Vyas, Mahesh .2020. “21 Million Jobs added in May”. https://www.cmie.com/kommon /bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2020-06-02%2011:43:41&msec=800https://debraj ray.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/RaySubramanian.pdf.